Since I started this blog, I have purposely avoided writing about certain St. Louis history topics. In the past eighteen months, people have suggested I write about various things like the InBev buyout of Anhueser-Busch, the Pope’s visit in 1999, and even the Edward Jones Dome (seriously?). Honestly, these are topics that just don’t interest me. They make me yawn. Other suggestions, like the 1904 World’s Fair and the Gateway Arch, are so familiar in St. Louis that I’m not sure I could make them interesting. I worry writing about them would make others yawn.

The category “I’d Rather Be Burned Alive” includes a topic someone suggested just a few weeks ago. On that day, I was asked to research why everyone in St. Louis always asks everyone else in St. Louis “Where did you go to high school?”

After informing my well-meaning and idea-challenged friend that I attended Elmira Free Academy (located about 900 miles to the east), and then asking where she went to high school, I rolled my eyes and politely declined.

(Damn! I succumbed to that tedious St. Louis high school inquiry after all.)

Anyway, there’s another category of St. Louis history topics that I’m saving for a rainy day. These are the big kahunas; the topics that I believe are very special in this city. I want to space these gems out over the next several years (or as long as I continue to beat myself up trying to write this blog). Examples include the Cahokia Mounds, the Lemp Caves (if I can ever get down there), Forest Park, Pruitt-Igoe, and the Camp Jackson Affair. Dozens more exist, which means I plan to force this blog down people’s throats for years to come.

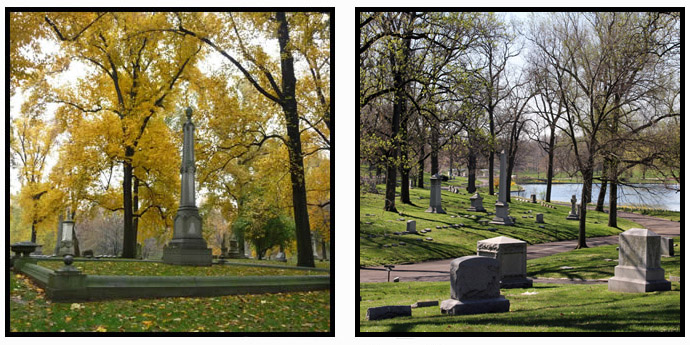

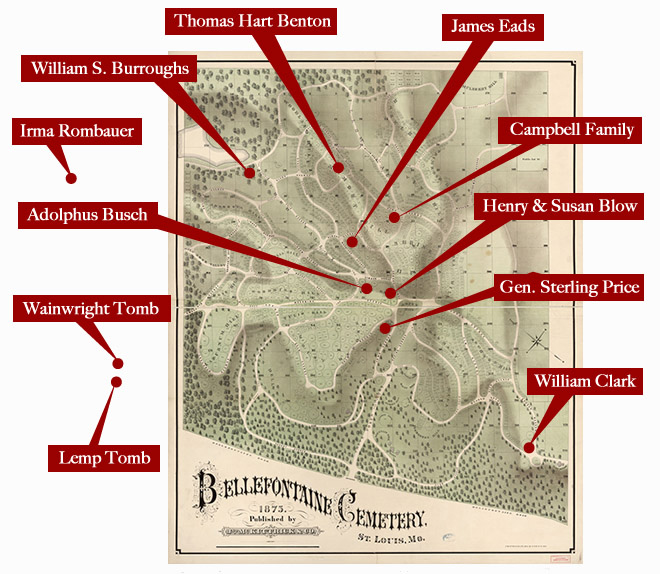

Well, I think it’s about time to dust off one of the good ones. A few weeks ago, I was the lucky recipient of a special tour of Bellefontaine Cemetery, the wonderful 314 acres in north St. Louis that holds as much history (literally) as any patch of ground in the Midwest. Over 87,000 people are buried there, and each one has a tale to tell. If you like Distilled History, get used to Bellefontaine. I plan to pluck stories out of this place for years to come.

Let’s kick this off by admitting that I adore cemeteries. I love to drive through them, bike through them, and tour them. I enjoy locating graves of notable people, as I’ve done for the Homer Phillips, Elijah P. Lovejoy, and Irma Rombauer posts in this blog. I sometimes go to cemeteries just to sit and read a book, admire the foliage, or even take a nap. I think they are big, wonderful parks of history.

A park-like type of cemetery such as Bellefontaine (and Woodlawn, the Elmira, New York cemetery that my fellow high school graduates should know), is considered a “rural cemetery”. These are cemeteries that primarily honor the dead, but are also designed to provide a welcoming and comfortable place for people to visit. That’s certainly the case at Bellefontaine. It is a peaceful and beautiful place to see. Containing more than 4,000 trees and over 180 species of trees and shrubs, Bellefontaine is not just a cemetery. It is also an accredited Level II arboretum.

The “rural cemetery” movement started in the mid-19th Century. Following a model set forth in Paris, the first rural cemetery in the United States was established in 1831 (Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts). Eighteen years later, Bellefontaine in St. Louis was established as the first rural cemetery west of the Mississippi River. Prior to Bellefontaine Cemetery, St. Louis buried their dead in plots around churches and in smaller, overcrowded cemeteries in and around town (many were located along current-day Jefferson Avenue).

St. Louis in the mid-19th century was growing rapidly. Along with overcrowding, many believed that air, water, and soil could become infected with disease if people were buried near population centers. Both concerns were further intensified in the summer of 1849 when a deadly cholera epidemic killed nearly 10% of the city’s population (note: future blog post). Suddenly, burying people farther away became a priority.

As a result, city leaders formed an association for the purpose of founding a large rural cemetery outside city limits. It was named after Fort Bellefontaine, a military garrison located about five miles northwest of St. Louis. Along the road to that fort sat the Hempstead farm. This 138 acre farm was purchased by the foundation, and the land became the first of three parcels that together now make up Bellefontaine Cemetery as we know it today.

The next significant step in the shaping of Bellefontaine Cemetery was the hiring of a renowned landscape architect named Almerin Hotchkiss. It was this man who created the master plan for the cemetery and gave it the look we still see today. He oversaw the building of the roads, landscaping, and overall maintenance of the grounds. Upon completing the overall plan, he remained in St. Louis as superintendent of the cemetery for the next forty-six years.

Perhaps the most significant monument in the entire cemetery (along with one of the better stories), is the Charlotte Dickson Wainwright Tomb. Universally regarded as an architectural masterpiece, the tomb was constructed in 1892 for the wife of millionaire and philanthropist Ellis Wainwright. Referred to in local press as “the most beautiful woman in St. Louis”, Charlotte Wainwright died suddenly of peritonitis at the young age of thirty-four. Her husband Ellis was emotionally devastated by her passing. In order to preserve her memory, Ellis Wainwright reached out to a particularly famous architect for a unique and exceptional design.

The result is one of the most significant designs from of one of history’s most important architects, Louis Henry Sullivan. Known as the “father of the skyscraper”, Sullivan was at the height of his fame when he was commissioned to design Charlotte Wainwright’s tomb.

When Charlotte Wainwright died, Louis Sullivan was already in St. Louis finishing another project for Ellis Wainwright. That building, which also bears Wainwright’s name and stands today at the corner of Chestnut and 7th in downtown St. Louis, is another topic I better be careful with if I choose to write about it. Considered by many to be the first skyscraper ever built, the 10 story Wainwright Building is a masterpiece. It was even featured in recent a PBS documentary as one of 10 Buildings That Changed America.

When Wainwright asked Sullivan for a preliminary design, he provided a sketch of a tomb that combines two classic forms, a half-sphere resting upon a cube. Inspired by the tomb of a Muslim Saint in Algeria, the form appears solidly Byzantine. Assisting Louis Sullivan with the design (particularly the interior) was his head draftsman, a promising young architect named Frank Lloyd Wright.

The simple cube and dome design is accented by a border of richly carved motifs and bronze grill doors. Windows adorn each side of the tomb, each surrounded by additional stone carvings. Interestingly, the name “Wainwright” appears nowhere on the exterior of the tomb. Placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970, it is often referred to as the “Taj Mahal of St. Louis”. The New York Times referred to it as a “major American architectural triumph”, and “a model for ecclesiastical architecture”.

Hugh Morrison, in his book Louis Sullivan, Prophet of Modern Architecture, writes:

…it is the most sensitive and the most graceful of Sullivan’s tombs, distinguished alike in its architectural form and its decorative enrichment. In the writers opinion, at least, it is unmatched in quality by any other known tomb.”

While the exterior is unassuming, the interior (that I was delighted to be able to see on my special tour) surges with subtle color, swirled marble, and flecks of gold. The walls and ceiling are covered with a beautiful patterned mosaic. Look above, and small angels dispersed among small mosaics seem to come and go depending on the point of view. Below, two burial slabs are inlayed in the floor to mark the final resting place for Ellis Wainwright and his wife Charlotte. Each is chiseled with a poem, Lord Tennyson for the husband and Anna Laetitia Barbauld for his wife:

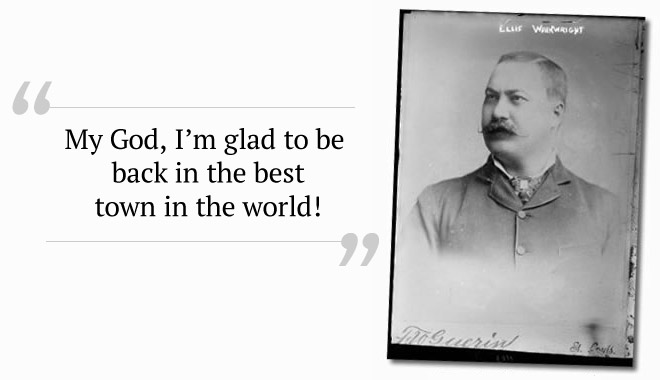

Despite having two architectural masterpieces named after him, things didn’t go very smoothly for Ellis Wainwright during his later years. While in New York in 1902, Wainwright learned he was being indicted for attempting to bribe several politicians as part of a business deal. Instead of heading home to face the charges, he fled to Europe. Although he lived lavishly in Paris for several years, his self-imposed exile took a toll on his health. He didn’t return to St. Louis until 1911 when the prosecuting attorney in his case had retired. He paid a bond upon arrival and proclaimed to the press that he was happy to be back. Ultimately, the charges didn’t stick and Wainwright was able to resume life as he wished.

Soon after, Wainwright moved to New York to be close to other business investments. In 1922, he shocked friends and associates by “adopting” a twenty-two year old woman named Rosalind Kendall (he was seventy-two). She took his name, called him “Daddy”, and became his constant companion. She lived in the apartment adjoining his on Park Avenue.

Not surprisingly, The arrangement didn’t last. When Wainwright’s efforts to make Rosalind a movie star proved unsuccessful, Rosalind moved on. She supposedly accepted a sum of money in return for relinquishing any claims to Wainwright’s estate. Upon Wainwright’s death, this arrangement was legally overturned, making Rosalind Kendall very wealthy.

In declining health, Ellis Wainwright returned to St. Louis in 1924. He turned his attention back toward his departed wife Charlotte, setting up an endowment at Bellefontaine to repair her tomb in the event of vandalism or earthquake. His behavior also became increasingly peculiar. During his final days at the Buckingham Hotel, servants were required to physically move him from room to room in order to avoid being seen by hotel maids.

Ellis Wainwright died on November 6, 1924 at the age of seventy-four. He was laid to rest next to his wife in the remarkable monument to them both in Bellefontaine Cemetery.

![]()

The reason why Ellis Wainwright had the means to build one of the first skyscrapers and the “Taj Mahal of St. Louis” is a good one. Like the familiar names in 19th Century St. Louis such as Busch and Lemp, Wainwright became rich as a result of beer.

When Wainwright was just twenty-four years old, he inherited his father’s Wainwright Brewery. Displaying a keen business sense, he secured his path to wealth by doubling profits within two years. He became even wealthier when he sold his brewery to a syndicate named The St. Louis Brewing Association (SLBA). Wainwright was named president and became responsible for managing day-to-day operations. The famous building that bears his name in downtown St. Louis today was initially built as a headquarters for the syndicate he managed.

With that in mind, it’s only appropriate to drink beer in honor of Ellis Wainwright, his lovely wife, and his epic tomb. Even better, I thought this post would provide a perfect opportunity to brew up a batch of my own.

First of all, I must admit that I am not an accomplished homebrewer. People who are familiar with the hobby know that it’s really nothing more than simple cooking. Well, I’m not a very good cook. But I can follow a recipe, and homebrew kits always come with recipes. I still brew from extract kits, and despite people insisting I move up to the world of “all grain” brewing, I haven’t done it yet. That day will likely come, because with each homebrew batch, I seem to add some additional piece of homebrew equipment that makes the process more fun. For those in the know, I introduced a stir plate and an outdoor burner for this batch. The result was an active primary fermentation that two days later had me scrambling for a blow-off hose.

Until I get to the next level, I’ll keep going with the real reason I started home brewing in the first place: Beer labels. Drinking the beer you make is fun, but naming the beer and designing the beer label is really fun. It’s probably why I’ll never keg it. As much as I hate washing and sanitizing forty-eight individual beer bottles, it makes my day to drink out of a bottle labeled as my own.

My beer may not taste as good as others, but I think my labels are top-notch.. This includes a new one featuring the exquisite tomb found in Bellefontaine Cemetery.

Sources:

Sources:

- Movers and Shakers, Scalawags and Suffragettes: Tales from Bellefontaine Cemetery by Carol Ferring Shepley

- St. Louis Brews: 200 Years of Brewing in St. Louis, 1809-2009 by Henry Herbst, Don Roussin, and Kevin Kious

- St. Louis: Landmarks and Historic Districts by Carolyn Hewes Toft and Lynn Josse

- Louis Sullivan, Prophet of Modern Architecture by Hugh Morrison

- National Register of Historic Places Registration Form – National Park Service

- Woo, William F., “Story Behind the Wainwright Building,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 23, 1966 p. 3J

I will read anything you write! Beautiful piece!

Thank you so much. That makes my day.

My last conversation with the late Dolph Orthwein, he exclaimed with a twinkle in both his voice and eye said “I just received a card from Bellefontaine Cemetery, and they asked if I wanted to drop in…” We both had a good laugh…and that was 5 years ago. Rest easy Dolph, you were a credit to your family.

This blog is becoming the best collection of on-line history that STL has….should you stop posting I would consider it a crime.

Great stuff. Bringsme back to riding hikes in Woodlawn. Merry Christmas

I hate autocorrect.