Ciao miei buoni amici! Saluti dall’Italia!

Ciao miei buoni amici! Saluti dall’Italia!

For this bit of Distilled History, I must ask my St. Louis readers to allow me another brief detour. I’ve been pampering myself in Tuscany for the past two weeks, and I haven’t had an opportunity to blow the dust off another St. Louis history topic. I’ll return to the stories of Mound City in due time, but for now I am fulfilling a lifelong dream of seeing Florence and Rome. As a student of history, these two towns have more to offer than just about any place in the world. To make up for my absence, I figured I could throw in some Distilled History while I’m here. It shouldn’t be that difficult, right? Since I’m reveling in the cradle of western civilization, I can’t help but stumble over great history, food, and drink.

It’s actually easier said than done. I’m very distracted. I’m trying to write this post while sitting in a luxurious 18th Century villa. There’s a swimming pool, palm trees, and half-naked lady statues scattered around me. The landscape before me is filled with rolling hills, vineyards, and round bales of hay. Our villa is located near the idyllic town of Montepulciano, an area known for producing some of the best wine in Italy. Worst of all, I’m currently battling an astounding hangover caused by too much of that Italian wine (along with grappa, birra, gin, bourbon, and a certain cocktail you’ll read about in a bit).

Fortunately, I found a topic to write about years before I even arrived here. While it would be easy to write about Italian monuments such as the Coliseum, St. Peter’s Basilica, or the Pantheon, these sites are secondary to me on this trip. Years ago, I watched a fascinating documentary about a Cathedral in Florence that fascinated me. Although not as recognizable as the previously mentioned sites, it’s a very big deal. Specifically, what sits on top of that church is what I had to see for myself.

I’m won’t go nuts doing research for this post. I’m in Italy, and I don’t want to do anything but bake in the Tuscan sun, drink myself tipsy, and look at very old things. All of the information for this post came from my vague recollections of the documentary, my climb up the dome, and the book Brunelleschi’s Dome by Ross King. If you enjoy superb non-fiction writing, this guy has the goods. His book Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling about the Sistine Chapel is also outstanding.

“Brunelleschi’s Dome” is how many refer to the cupola atop the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore. It is the “Duomo di Firenze”, or the Cathedral of Florence. Construction of this cathedral began 1296, and the initial plans called for the largest dome ever constructed to sit atop it. Sounds like a great plan, but the architects faced a significant problem: Nobody knew how to build a build such a massive dome.

Despite the lack of dome building knowledge in the late thirteenth century, the so-called experts decided to go ahead and build the cathedral anyway. They figured that since it would take decades to build the foundation and walls, they had plenty of time to figure out the dome problem before constructing it was necessary.

Oops. Not so fast. When the cathedral was ready for the dome in 1380 (nearly 100 years later), they still didn’t have a solution. The cathedral would sit open to the elements for another forty years before one man introduced a plan worth trying.

Perhaps it was a certain mindset in Florence at the time that gave the original architects such optimism. After hundreds of years of ignorance and suppression of knowledge during the Middle Ages, a cultural movement was blossoming in Italy. Florence in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries introduced a resurgence of learning based on classical knowledge. Instead of writing the ancient Greeks and Romans off as pagans, great thinkers looked to them for inspiration. This re-birth or “Renaissance” brought humanism back into the mainstream. The dome that was built atop the Florence Cathedral would become one of the most important accomplishments in the early years of that movement.

The inability to build a large dome is surprising since one had been standing tall in Rome for nearly 1,000 years. The Pantheon, a self-supported concrete dome 142 feet wide and weighing 5,000 tons, was built by Emperor Hadrian in 126 AD. Despite having a full-size model at their disposal, nobody could figure out how to build it again.

That is, until Filippo Brunelleschi came along.

Born in Florence in 1377, Brunelleschi grew up in the shadow of the Florence Cathedral as it was built. Initially trained as a goldsmith and clockmaker, Brunelleschi soon displayed an unparalleled genius in art, architecture, engineering, and mathematics. Along with the dome he’d make famous, Brunelleschi is also credited with discovering the mathematical laws of perspective. Another concept lost since Greek and Roman times, perspective gave artists the ability to accurately represent three-dimensional images on a two-dimensional surface. This discovery (or rediscovery) radically changed the direction of artistic impression during the Renaissance.

Eventually, a guild in Florence announced a contest for entrants to submit plans to complete the unfinished dome. Brunelleschi, who had studied the Pantheon closely with his good friend Donatello, jumped at the opportunity. It took some convincing, but Brunelleschi was eventually able to secure the commission for himself.

Brunelleschi was a character (to say the least). He was brilliant, competitive, combative, and paranoid. He was so convinced that his ideas and designs would be stolen, that he refused to explain exactly how he would build the dome. Despite being called an “ass” and a “babbler”, he indefatigably insisted he could do it.

The original plan called for an octagonal dome 171 feet above the floor of the cathedral and spanning 144 feet (two feet wider than the Pantheon). Adding to the challenge, support and centering the dome from underneath wasn’t possible. Materials for such an enormous scaffold weren’t available, and church leaders insisted that the interior of the cathedral remain open and accessible for services during construction. The dome would have to support itself as it climbed into the sky.

Brunelleschi rose to the challenge with a myriad of ingenious solutions. In nearly every phase of construction, he overcame hurdles with methods that had never been used before. Even the mathematics used to determine such significant building stress wouldn’t be known for hundreds of years. His accomplishment is all the more impressive considering what little architectural knowledge was available at the time.

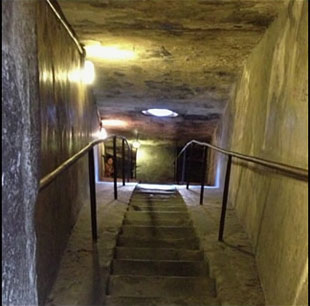

The most important aspect of his design is that the dome is actually two domes. An inner shell is made of sandstone and marble, and it acts as the main load-bearing structure. The inner shell is also obviously smaller, but that fact is not noticeable to the naked eye. It is protected by a larger outer shell constructed of brick and mortar. The space between the two shells contain ribs for additional support (and the staircase that I had longed to climb).

In constructing the inner shell, the biggest problem facing construction was overcoming “hoop stress”. As a dome’s construction goes higher, more weight is forced upon the base. Unchecked, this can cause the base of the dome to “spread” and ultimately collapse under its own weight.

I’m no architect, but “spreading” sounds bad for domes built 200 feet off the ground.

To counter hoop stress, Brunelleschi devised a system of horizontal iron, stone, and wooden “chains” that act like metal hoops around a barrel. Built into the inner shell at various levels, these chains squeeze the dome and distribute weight to the eight corners of the octagon. Even today, full details of Brunelleshi’s chain designs are not fully understood. Since the chains are built into the inner shell, they aren’t visible to study with the naked eye.

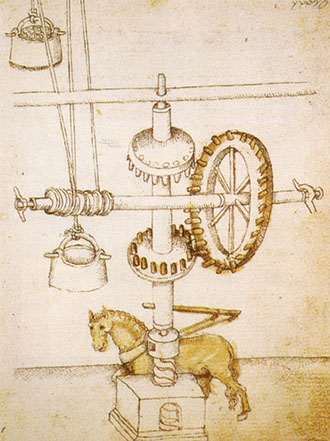

Another hurdle was how to get thousands of blocks, brick, and mortar up into the sky. Nobody had figured out how to do that either, so another contest was announced. Brunelleschi won the blue ribbon again, designing a remarkable lift and crane system. The hoisting power was provided by oxen that moved in a circle around the base of a lift. Sounds simple enough, but the problem was getting the lift back down to earth. Oxen don’t travel in reverse, and unhitching and reversing the team after each lifting session was a giant hassle. To solve this, Brunelleschi designed a reverse gear that could be shifted manually. This allowed the oxen to continue moving happily along (well, maybe not so happily), in one direction. Additionally, Brunelleschi even gave his lift variable speeds. This allowed heavier blocks to be lifted slower while lighter materials could be raised quickly.

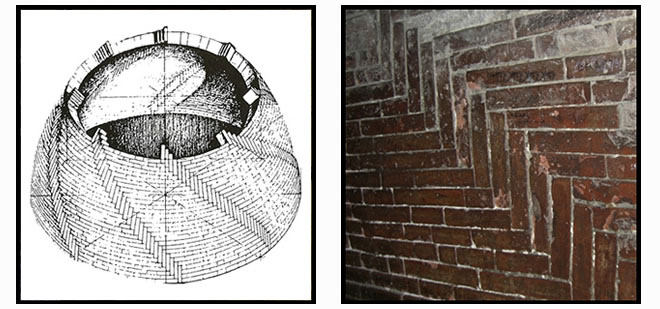

The eight brick sections of the outer shell also presented a unique problem. As the dome progressed higher, the brick walls angled inward at an increasingly perilous angle. Without support from beneath, a solution was needed to keep the angled bricks in place while the mortar dried. No scaffold also meant that twitchy masons had to build the walls while perched more than two-hundred feet off the ground. Without missing a beat, Brunelleschi had a solution for this problem as well. He used a herringbone (think zigzag) pattern that placed bricks vertically at regular intervals in each row. These vertical bricks act like bookends to provide support for each row of horizontal bricks.

Sadly, I can barely understand that concept, let alone explain it. Being a guy who simply likes to drink and find good history, physics makes my head hurt. I’m going to have to defer to Ross King on this one. If anyone needs further information how Brunelleschi worked this out, pick up Mr. King’s book and turn to page ninety-eight. I can’t add anything other than to say that I think herringbone brick is kinda pretty.

After sixteen years of construction, the dome was completed in 1436. Except for the one mason that fell to his death, everyone agreed that Brunelleschi had pulled off a remarkable feat. Single-handedly, he pushed architecture and the science of building light years ahead of where it had been. His design would become the standard for all Baroque and Renaissance dome construction going forward. Years later, when when Michelangelo designed the dome atop St. Peter’s Basilica, he credited Brunelleschi’s dome as his inspiration.

Filippo Brunelleschi died in 1446. His legacy seure, he was even given the honor of being entombed in the cathedral he helped build. Visit Florence today and you can also find a fine statue of Brunelleschi that sits outside. It depicts a man gracefully looking up and admiring the dome he built.

Nearly six-hundred years later, Brunelleschi’s dome is as impressive as ever. My good friend Liz and I also found out it’s one hell of a climb. As we huffed up the 400-plus steps, we found twisting stairwells becoming increasingly darker and narrower. The stairs wind between the two shells, so one can even say they have climbed through history when they get to the top. The effort is more than worth it. As you climb higher, you’ll get to view the interior frescoes close-up, you can peer through small exterior portals allowing beams of light in, and can run your fingers along the herringbone-patterned brickwork. When you finally emerge at the top, you are greeted with stunning panoramas of the city of Florence. The view isn’t likely to be much different from what Brunelleschi saw himself.

![]()

After an American climbs an Italian cathedral, it’s only appropriate that an American orders an Italian cocktail. I almost went with grappa for this post (so very delicious), but I needed something refreshing after that climb.

With its distinctive dark red hue, Campari even looks sweet and delicious. It’s actually quite bitter, made from a secret recipe of aromatic herbs, fruit, barks, and other unknown botanicals. It even once contained crushed cochineal insects to give it the scarlet color its known for (this process has recently been replaced with artificial coloring). When I was a kid, I remember insisting that father let me try a sip of his Campari and soda. My face contorted into a sneer of disgust, and I couldn’t fathom why he even pretended to enjoy it. My father knew his alcohol though, and thirty years later, Campari became a steady partner in my rambles through Florence and Rome.

A man named Gaspare Campari invented Campari in northern Italy around 1860. It is a mild bitters-type aperitif, a drink Italians sip to help stimulate their appetite before one of their epic meals. Italians usually drink it in a cold glass with a splash of soda. I prefer Campari as an ingredient in cocktails, notably the Negroni and the Americano. Adding Campari to a Manhattan also creates a delicious variation.

The Americano, my cocktail of choice after the climb, is a simple and refreshing cocktail, especially for a hot summer day. When I return to St. Louis and the weather is sure to be unbearable (sigh), an Americano is another good cocktail to help beat the heat. It should be stirred and served on the rocks, but I’ve occasionally seen it served straight up in a cocktail glass. It’s usually served with a slice of lemon or orange as a garnish.

Other than a few “grazies” and “ciaos”, I don’t speak Italian. I gave it a shot while wandering the streets of Florence, but I wasn’t completely surprised to find my Americano order result in a cup of coffee placed in front of me. Thinking I screwed something up, I soon learned I was on the money. An “Americano” or “Café Americano” is also a term used to describe espresso mixed with hot water.

My espresso was delicious, but I needed a kick after climbing 400 steps. I sheepishly drank my café Americano and moved on to another bar where I made sure to point at the bottle of Campari when ordering.

No problems with this order, and I soon found myself sitting back and enjoying my cocktail. From my seat, I was able to look up and admire Brunelleschi’s dome that towered into the sky before me.

Florence was my favorite of the Italian cities, and I devoured Ross King’s book. Glad you got to experience the marvel that is Firenze!

Such a wonderful city. No better place for a history buff!