This blog has been opening some fun doors lately.

Just in the last few months, I’ve been asked to speak at a museum, lead a bicycle history tour, emcee a fundraising event, and even write a book. It’s all great stuff, but it’s presented me with a huge problem. All of this extra stuff has made it extremely difficult to churn out Distilled History posts on a regular basis. So, I recently decided that I just had to just sit down and write. Don’t get all research-y like I’ve been lately. Just write… and do it quickly.

And I thought I could do it. That is, until I ran into B.F. Young and his St. Louis Ale Brewery.

B.F. Young was an ale brewer in St. Louis 140 years ago. His brewery was unique, because at a time when St. Louis brewers overwhelmingly produced lager, Young seems to be one of few that produced ale. Beer men like and William Lemp and Julius Winkelmeyer took one look at those cool, dark caves beneath the city and wasted no time building towering lager breweries on top of them. With a large (and thirsty) German population in St. Louis clamoring for the cold-fermented variety of beer they made, a thriving local industry was born. If a St. Louisan living in 1875 wanted a glass of ale, few options were available. The 1875 St. Louis City Directory lists nearly thirty brewers making lager. The ale brewers, including B.F. Young, are listed separately under their own heading, and they number only two.

According to Henry Herbst, Dan Roussin, and Kevin Kious in their book St. Louis Brews, very little is known about B.F. Young. The authors note that during the late 1870’s, Young’s brewery produced about 800 to 1,100 barrels of ale each year, which wasn’t much compared to the many lager breweries scattered around him (in comparison, Lemp’s Western Brewery cranked out over 61,000 barrels of lager in 1877). However, B.F. Young became a particular interest of mine because in the year 1875, he was brewing ale at the same time two guys were putting the finishing touches on a very special map. And more specifically, I couldn’t find B.F. Young on that very special map.

According to Henry Herbst, Dan Roussin, and Kevin Kious in their book St. Louis Brews, very little is known about B.F. Young. The authors note that during the late 1870’s, Young’s brewery produced about 800 to 1,100 barrels of ale each year, which wasn’t much compared to the many lager breweries scattered around him (in comparison, Lemp’s Western Brewery cranked out over 61,000 barrels of lager in 1877). However, B.F. Young became a particular interest of mine because in the year 1875, he was brewing ale at the same time two guys were putting the finishing touches on a very special map. And more specifically, I couldn’t find B.F. Young on that very special map.

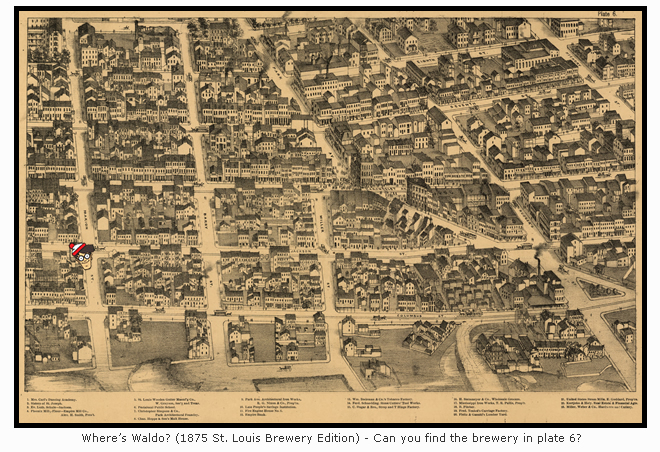

The map I’m referring to is Pictorial St. Louis: The Great Metropolis of the Mississippi Valley, a Topographical Survey Drawn in Perspective A.D. 1875. Created by publisher Richard Compton and artist Camille Dry, Pictorial St. Louis is widely regarded as one of the most extraordinary maps ever created. For those not familiar with it, check out this post I wrote about it back in 2012. It was also recently featured in an exhibit titled “Mapping St. Louis” at the Mercantile Library. And most importantly, it’s now featured in a fantastic new exhibit titled “A Walk in 1875 St. Louis” at the Missouri History Museum.

Since Compton & Dry’s map has been getting so much attention lately, I decided to revisit their opus and have a bit of boozy fun. I hatched an idea to identify each and every brewery drawn within the 110 individual plates that make up Compton & Dry’s map. It seemed like a simple plan, since much of the brewery identification had already been done by Compton and Dry in the labels on each plate or in the index of the book (which is how the map was published). I figured all I’d need is to whip up a few pretty graphics, determine where the breweries would have stood today, and of course, get a drink to tie it all together.

Wrong.

I now find myself sitting in front of spreadsheets, pages of scrawled notes, maps, printouts, photographs, computer screens, an empty glass of beer (of course), and I still can’t say for sure how many breweries even existed here in 1875. I have one credible source that tells me twenty-two breweries operated in St. Louis that year. I have another source that tells me twenty-nine. A third lists twenty-five. Suddenly, I realized I was in trouble.

In the 1870’s, the brewery industry in St. Louis, like the city itself, was in a constant state of flux. The authors of St. Louis Brews should be commended for even attempting to document each of the breweries that closed, opened, moved, re-branded, re-named, burned down, were sold off, disappeared, or even exploded. The forks in the road are endless. Joseph Schnaider was a co-founder of the Green Tree Brewery, but in 1875 he’s the owner of the Chouteau Avenue Brewery. Henry Grone decided one day to stop calling his brewery the Clark Avenue Brewery and just name it after himself. Hyde Park, a north city brewery recalled by many St. Louisans today, was known as the Emmett Brewery in 1875. In the same year, Eberhard Anheuser still called his brewery the Bavarian Brewery and William Lemp called his the Western. Things were getting complicated.

In the 1870’s, the brewery industry in St. Louis, like the city itself, was in a constant state of flux. The authors of St. Louis Brews should be commended for even attempting to document each of the breweries that closed, opened, moved, re-branded, re-named, burned down, were sold off, disappeared, or even exploded. The forks in the road are endless. Joseph Schnaider was a co-founder of the Green Tree Brewery, but in 1875 he’s the owner of the Chouteau Avenue Brewery. Henry Grone decided one day to stop calling his brewery the Clark Avenue Brewery and just name it after himself. Hyde Park, a north city brewery recalled by many St. Louisans today, was known as the Emmett Brewery in 1875. In the same year, Eberhard Anheuser still called his brewery the Bavarian Brewery and William Lemp called his the Western. Things were getting complicated.

To cobble it all together, I hit the libraries for more source material. While pouring through city directories, I found breweries listed under the proprietor’s name (Wetekamp & Co), but not the brewery name (Laclede Brewery). A few had offices in a completely different part of the city (B.F. Young, Lemp), making it difficult to determine which location was the office and which was the brewery. For every Anthony & Kuhn that brewed neatly under one name and in one place, I found a National Brewery that appeared and disappeared throughout the years. Three breweries (Bavarian, Western, and Pittsburg) complicated things by operating satellite breweries in other parts of town. Others (Uhrig) had caves in other parts of town. But in Pittsburg’s case, their cave was actually a satellite.

As I dug deeper, I juggled Griesediecks, Oberts, Stifels, Staehlins, Tinkers, Eckerles, Feuerbachers, Schnaiders (with an a), and Schneiders (with an e). Many of them owned breweries drawn on Compton and Dry’s map, but aren’t listed in city directories. Others owned breweries that are listed in city directories, but aren’t drawn on the map. Some breweries are labeled on the map while others aren’t. One brewery (Bremen) seems to have stood exactly between two plates. It’s not drawn on either, so I guess it sits in some sort of map void.

Determining where the breweries would have stood today had my head spinning since St. Louis street renaming and street renumbering has been extensive since 1875. I drove by Cass and 19th thinking I found where the Lafayette Brewery once stood, only to learn a day later that 19th is now known as 18th. A section of 21st Street used to be named Parnell, or maybe it’s the other way around. Lemp used to be Buena Vista. 10th was known as Buell in one part of the city and Menard in another. Carondelet Avenue is now Broadway, and Second Carondelet is now 18th. If this didn’t confuse me enough, city directories constantly goofed addresses. Laura Milentz’s weiss brewery is listed at 1535 Carondelet in 1874, but she’s across the street in 1875. My pal B.F. Young gets three different addresses in three different directories: 212 N. 3rd Street, 121 N. 2nd Street, and 514 N. 2nd Street.

Teetering on the brink of madness, I finally found B.F. Young. There he was all along, mocking me from the middle of plate 4. Compton and Dry even labeled it, but since a 140 year-old typo had me rummaging for an intersection two miles away that didn’t exist, I never considered simply looking the map’s index again. Sigh.

In the end, I’m (cautiously) optimistic that I have identified the twenty-nine St. Louis breweries that pumped out thousands and thousands of barrels of delicious beer in 1875. I also think I’ve accurately pinpointed each of them (well, most of them) on Compton & Dry’s epic map. Please note that I only include breweries inside the borders of that map. Since Compton and Dry didn’t include Carondelet, I don’t include Carondelet’s Southern Brewery.

I’m sure a beer historian or two may challenge what I’ve done here, and I welcome any input or corrections. I even know a few of them who could have made this entire task much easier. I probably should have asked for more assistance, but I do love a good history hunt. I’ve had as much fun with this post as any I’ve written.

Finally, twenty-nine breweries are a bit much to cover in one post, so I’m splitting it up. The fifteen “Northern and Central” breweries, as I call them, are presented in this post (in no particular order). The fourteen “Southern” breweries (which make up the heart of St. Louis brewing) will come in a second post in a few days (update: it was posted 6/17/15).

Finally, twenty-nine breweries are a bit much to cover in one post, so I’m splitting it up. The fifteen “Northern and Central” breweries, as I call them, are presented in this post (in no particular order). The fourteen “Southern” breweries (which make up the heart of St. Louis brewing) will come in a second post in a few days (update: it was posted 6/17/15).

With all of that said, here we go.

Lafayette Brewery – Plate 52

Lafayette Brewery – Plate 52In 1875, the Lafayette Brewery stood at the southeast corner of Cass Avenue and 19th (now 18th). It was located just a block or so east of the noteworthy James Clemens house.

The Lafayette Brewery can be seen in Pictorial St. Louis in the lower left corner of plate 52. Today, a housing development occupies the site.

![]()

Emmett Brewery – Plate 76

Originally known as the Hecker Brewery, the facility drawn and labeled on plate 76 would eventually become the Hyde Park Brewery, a name familiar to many St. Louisans today. In 1875, it was a smaller operation known as the Emmett Brewery. In the 1875 St. Louis City Directory, it’s listed at the corner of Salisbury Avenue, between 15th and 16th streets.

In 2015, it’s the corner of Salisbury and North Florissant in north St. Louis. An unknown business now occupies the site.

![]()

Bremen Brewery – Plate 77 (well, it should be)

Bremen Brewery was operated by a man named Tobias Spengler and was the northernmost brewery that operated in St. Louis in 1875.

Bremen Brewery is listed in the 1875 St. Louis City Directory at 3823 Broadway. However, no brewery (or anything resembling a brewery) can be found in that area on Compton & Dry’s map.

Examination of a 1909 Sanborn fire insurance map shows an “Abandoned Brewery” at 3823 Broadway. Located at the northwest corner of Broadway and Bremen Avenue, there is little doubt it is the old Bremen facility.

Why isn’t it drawn on the 1875 map? What seems to be a draftsman’s error may provide a clue. On plate 77, where the intersection and brewery should be drawn at the bottom edge of the plate, Bremen Avenue is mislabeled as Maguire Street. It’s not much of a theory, but perhaps one of Camille Dry’s artists was simply looking at the wrong road.

![]()

Union Brewery – Plate 41

Union Brewery – Plate 41

In 1875, the Julius Winkelmeyer & Company was one of the larger brewers in St. Louis. Also known as the Union Brewery, the facility was located on Market street, just east of Joseph Uhrig’s Camp Spring Brewery.

Like many others, Winkelmeyer’s brewery benefited from natural caves that existed directly below his brewery. The cooler temperatures in these caves provided an ideal environment for making lager.

The Union Brewery is drawn and labeled on plate 41 of Compton & Dry’s Pictorial St. Louis. Today, the central branch of the United States Post Office occupies the site on the western edge of downtown St. Louis.

![]()

Uhrig’s Brewery – Plate 41

Originally known as the Camp Spring Brewery, Joseph Uhrig’s Brewery stood at the corner of Market and 18th, the same corner where Union Station stands today.

Uhrig was also known for “Uhrig’s Cave”, a natural cave located about a half mile away at the southwest corner of Jefferson and Washington Avenues. There, Uhrig built a famous beer garden, malt house, and entertainment venue on top of the large cave that stored his beer.

Uhrig’s brewery is drawn on Compton & Dry’s plate 41. Uhrig’s Cave is drawn on plate 53.

![]()

Franklin Ale Brewery – Plate 41

Franklin Ale Brewery – Plate 41

One of two ale breweries listed in the 1875 St. Louis City Directory, the Franklin Ale Brewery stood on the east side of 17th Street between Market and Clark.

Owned by a man named John Fleming, the Franklin Ale Brewery was a small operation that brewed ale exclusively.

The Franklin Ale Brewery is drawn and labeled on plate 41 of Pictorial St. Louis. Today, the site is occupied by an office building just west of the Scottrade Center.

![]()

Clark Avenue Brewery – Plate 53

Drawn and labeled as the Clark Avenue Brewery on plate 53 in Pictorial St. Louis, the brewery actually carried the name “H. Grone and Company” in 1875.

One of the top-ten beer producers in St. Louis when Pictorial St. Louis was published, the 1875 St. Louis City Directory places the brewery at 2311 Clark Avenue.

If the Clark Avenue Brewery existed today, it would stand either on top of or just west of the Pine Street access road to Highway 64.

![]()

Laclede Brewery – Plate 53

In the 1875 St. Louis City Directory, the Laclede Brewery is listed under its proprietor’s name, August Wetekamp. The listing places the brewery at the southwest corner of Walnut and 22nd.

![]()

Chouteau Ave. Brewery – Plate 40

Chouteau Ave. Brewery – Plate 40

Located on plate 40 of Pictorial St. Louis, the Chouteau Avenue Brewery is the only brewery that has been previously featured in Distilled History.

In 1875, the Chouteau Avenue Brewery was one of the larger breweries in town. Operated by Joseph Schnaider, it also featured an enormous beergarden that could entertain thousands of thirsty beer drinkers at once.

Although not visible on the map (it was built just after publication), the malt house for Schnaider’s brewery still stands across the street at the corner of Chouteau and 21st Street.![]()

City Brewery – Plate 44

In 1875, the City Brewery was located at 1901 North 14th Street. It’s proprietor was a man named Charles Stifel, well-known St. Louis due to his involvement in the Camp Jackson Affair. A supporter of the Union in the Civil War, Stifel formed his own German militia and drilled them in the malt house of his brewery. When his men clashed with pro-southern civilians in May 1861, nearly thirty people were killed.

His brewery once stood at what is now the northwest corner of 14th and Howard Streets. Today, a scrap yard occupies the brewery’s former location.

![]()

Liberty Brewery – Plate 74

Liberty Brewery – Plate 74Located at the southeast corner of Dodier and 21st Street, Liberty was one of the smallest breweries operating in St. Louis in 1875.

Although unlabeled on plate 74, the 1875 city directory places Liberty Brewery at the same corner where a manufacturing facility (or maybe a brewery) has been drawn. Further examination of a 1909 Sanborn map also confirms a brewery once existed at the same corner. Unless I’m told otherwise, I think it’s Liberty.

In 2015, the corner hosts an empty lot in the St. Louis Place neighborhood.

![]()

Fritz & Wainwright Brewery – Plate 23

Fritz & Wainwright Brewery – Plate 23

Labeled “Fritz & Wainwright” on plate 23 in Pictorial St. Louis, the massive brewery that once stood just south of downtown was actually named “Samuel Wainwright & Company” in 1875. It was the third largest producer of beer behind Lemp and Anheuser in 1875.

That name is familiar to many St. Louisans. Ellis Wainwright, the brewery’s owner, is the same man who commissioned architect Louis Sullivan to design and build the famous Wainwright Building that now stands in downtown St. Louis.

In 1875, his brewery took up an entire city block, bordered by Cerre, Gratiot, 9th and 10th Streets. In 2015, the site is a parking lot for the Purina Corporation.

Fortuna Brewery – Plate 51

Drawn on plate 51 of Pictorial St. Louis, Joseph Ferie’s Fortuna Brewery was one of the city’s smallest breweries in 1875. It’s listed in several city directories at 1906 Franklin, at what is now the southwest corner 19th and Dr. Martin Luther King Drive.

The exact structure on the map is a best guess. It’s not labeled by Compton and Dry, and the structures drawn at the address don’t seem to resemble breweries at all.

Today, no structures remain on the corner at all. It is an empty lot.

![]()

Hannemann & Deuber Brewery – Plate 74

Like Bremen, Hannemann & Deuber seems to land right at the edge of two adjacent plates (74& 75).

Compton and Dry didn’t label it, but it is listed in several city directories at the southwest corner of 20th and Dodier. Today, 20th is 25th, which should place just east of Liberty Brewery on the south side of the block.

However, other sources (including a printed advertisement included in St. Louis Brews) provides a specific address of 2543 and 2545 Dodier, that would place the brewery on the north side of Dodier, across the street from Liberty Brewery.

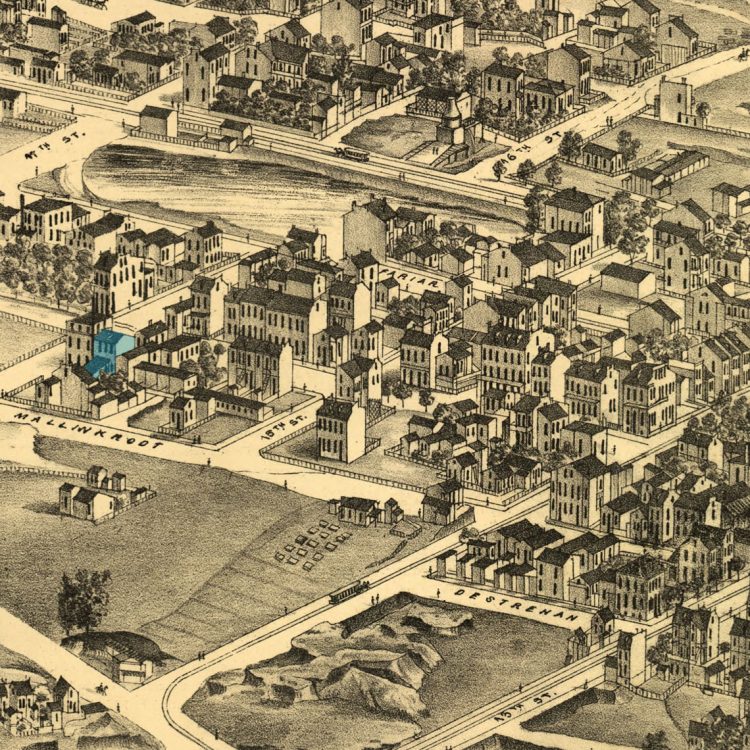

St. Louis Ale Brewery – Plate 4

St. Louis Ale Brewery – Plate 4

Last but not least, B.F. Young’s ale brewery is the one that drove me nuts all along. It’s identified and labeled on plate 4 of Pictorial St. Louis. Young is one of two breweries (along with Fleming’s Franklin Brewery) listed specifically in the 1875 St. Louis City Directory as an “Ale Brewer”.

A few different addresses appear in different sources for this brewery, and not a trace remains of any of them. The entire area was razed to make room for the Gateway Arch. If I had to pick a spot, I’d guess B.F. Young once brewed somewhere to the southwest of the Arch’s southern leg.

![]()

For additional (extensive) information about these breweries, how they came to be, and how they faded away, look no further than the book that acted as my guide throughout all of this. St. Louis Brews, 200 Years of Brewing in St. Louis, 1809-2009 will provide tell you everything you need to know about beer history in St. Louis. Even better, I’m hearing rumors a second edition may be in the works.

Click here for the Map that Drove Me to Drink, Part II

The ghosts of history that you awaken all over this city are fantastic. Thank you for another great post. Austrinken!

First in Booze, First in Shoes, Last in the American League. (Well known saying about St. Louis, before the Browns moved to Baltimore and became the Orioles.

And it’s a good one! Thanks for reading 🙂

Wonderful post! I really enjoy your blog, no matter how long it takes! Keep them coming.

bravo my friend …thank you!

Really enjoyed this post.

First, let me tell you that these maps look spectacular. Really a jump back in time. And second, your history hunting is fascinating in itself. I’m just sad that so little of these operations seems to be still in existance.

Great work. Seriously.

You may also want to mention that Louis Sullivan designed the Wainwright mausoleum in Bellefontaine Cemetery

You left much of the Lafayette Brewery unshaded. If you look at the photo of the Brinckwirth-Nolker Brewery on beerhistory.com, you will see that there is more to the complex. There are stables across the street. The Lafayette Brewery used dappled-grey Belgian working horses to haul their beer wagons around the city. The small houses to the southeast were built for workers by Mrs. Fredericka Brinckwirth. Her son, the young man pictured on the far right of the photo of the men of the Lafayette Brewery, Built more row houses just around the corner on 20th and Madison, which still stand today in excellent condition. It is seldom remembered that the Lafayette Brewery was the first modern brewing plant built in the city: 1858, six years before the Lemp plant of 1864; same architects.

Thank you! That is some great information. I wrote this post several years ago, but I’ll try to get it updated (and give you credit, of course). Prost!

Breathtaking bit of StL beer scholarship. As a 20+ year denizen of the city, I find your blog required reading.

Thank you! That means so much. I’ve struggled to get posts out lately, but comments like yours may light a fire under me. Cheers!

This is an amazing blog post about a super exciting lucrative time in St Louis’s history, especially for many German immigrants! My ancestors were the Grones who married with Griesediecks, Brinckwirths and Damhorsts, all brewing families, and it’s amazing to see the plates with the actual breweries in that St Louis map! I love history and all the imagery that we can collect to remember it!