Once again, despite this blog never making me a single dime, my life continues to become richer as a result of it. This time, it’s in the form of discovering how special that old bridge is that crosses the Mississippi. I’m sure when I first looked at it when I moved to St. Louis, I didn’t give it much thought.

But at this exact moment, I find myself staring at stacks of notes, books, photographs, and drawings of this city’s landmark bridge. In the past few weeks, I’ve stared at it, biked over it, sketched it, toasted to it, and even joked that I am awesome enough to survive jumping off it. What it all means is that I have way too much information to shove into a single blog entry. My dear mother chides me because my posts are too long as it is, but how can I keep that bridge, the man who designed it, and the drink to celebrate them both under 2,000 words?

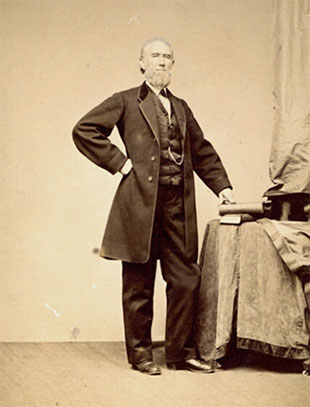

I can’t, so I came up with a plan. Like my Elijah P. Lovejoy posts last year, I think certain St. Louis history topics simply require a bit more love than others. For James Eads and his bridge, I’m going to write a couple, or maybe a few, and I’m going to post them all in a row. The good news is that most of my research is done (the biggest time consumer), so all I have to do is write, edit, and of course, drink.

Before I jump in (figuratively), I have to take a moment to clear something up. In discussing the Illinois & St. Louis Bridge (its original name), I often hear fellow St. Louisans confidently make a completely incorrect claim:

The Eads Bridge was definitely not the first bridge to span the Mississippi. It was the first one at St. Louis, and it contained several notable firsts in its design and construction, but it definitely wasn’t the first to span the river.

The Eads Bridge was definitely not the first bridge to span the Mississippi. It was the first one at St. Louis, and it contained several notable firsts in its design and construction, but it definitely wasn’t the first to span the river.

Perhaps people wouldn’t look to attribute unfounded facts to what the Eads Bridge is above the water if they only knew how special it is under the water. For that reason, I’m going to start my Summer of Eads with the story of the two massive limestone piers that hold it up. Specifically, I’m going to start with the story of the men who suffered building them. It’s a tragic story that I found particularly fascinating while researching every aspect of the structure. It’s also an unusual place to begin this bit of history, but like my new pal Amanda, I do tend to follow the unbeaten path.

Although he had never built a bridge before, James Eads knew the river better than anyone. His full story will come later, but it’s that point that must be noted here. The Mississippi is big and cranky. While it made many a riverboat pilot rich in the 19th century, it swallowed up just as many with its unpredictable currents and flows. As a young man, James Eads made his fortune walking around the bottom of it, salvaging wreckage in a diving bell of his own design. He knew first-hand how quickly the Mississippi could move something, and he had to be certain his bridge didn’t move. Sitting two massive bridge supports on silt and mud deposited by river currents wouldn’t cut it. They had to sit on bedrock.

During a trip to Europe in 1868, he witnessed first-hand a relatively new technology that he decided to employ in his own bridge, the pneumatic caisson.

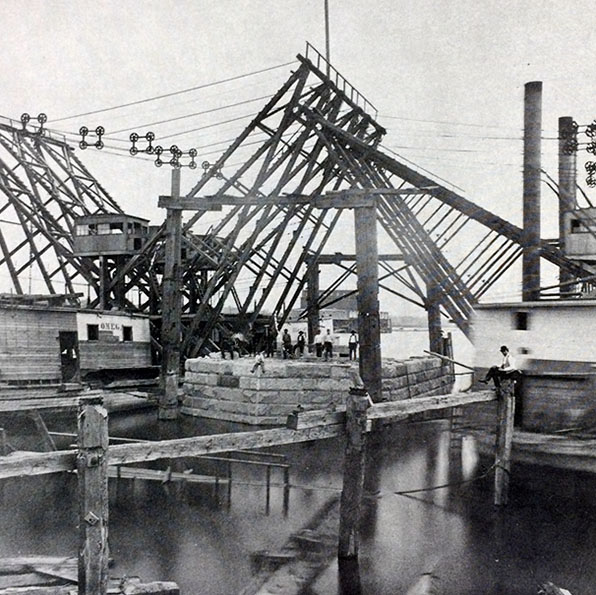

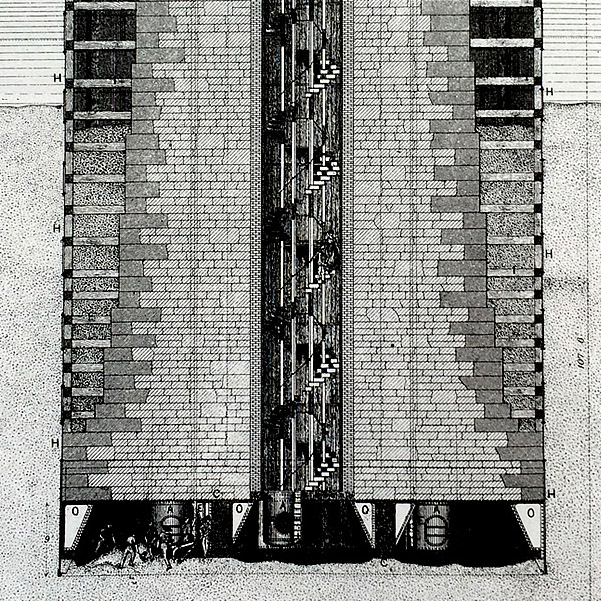

Caissons are watertight retaining structures. To work in depths of water, pneumatic caissons are sealed at the top and filled with compressed air. Sealed workspaces created by caissons allowed laborers (referred to as “submarines”) to work at the base of a bridge pier, on the riverbed, by digging up silt and sending it to the surface through pneumatic tubes. As the men dug towards bedrock, huge limestone blocks were piled on top of the caisson, thus building the pier at the same time the caisson pushed deeper into the riverbed. When it hit bedrock, the structure was leveled and the air chambers were filled with concrete. The concrete-filled caisson then became the base of the finished pier.

Pneumatic caissons offered an unprecedented level of efficiency, but at the time, only two bridges in the United States had been built using the technology. Neither came close to the size and depth required in Eads’ bridge design. Even today, the pneumatic caissons used in constructing the Eads Bridge are among the largest ever built.

When the east caisson was launched and sunk to the sandy river bed in October 1869, two engines on the surface went to work pumping compressed air into the chamber far below. This pressurized air compensated for leaks and provided a breathable workspace for laborers below. To get into the chambers, workers descended through a candle-lit spiral staircase and entered an airlock. When the airlock was sealed, an alternate door leading to the chamber was opened. The men could then climb out and begin work at the riverbed.

As workers dug through the sandy riverbed and the caisson sank deeper, air pressure increased to compensate for the higher water pressure outside. When the east caisson hit bedrock in February 1870, the air pressure inside the chamber measured fifty pounds per square inch. That’s over three times the “normal” air pressure a person experiences at sea level.

At first, these pressurized compartments were a source of wonder. Eads himself frequently led friends, politicians, and curious St. Louisans down through the spiral staircase and into the air chambers at the bottom of the river. While there, visitors experienced an eerie atmosphere, water dripping from above, the hissing of escaping air, and a nearly intolerable odor. While many found the experience wholly terrifying, others found amusement. The increased air pressure caused voices to sound nasal and high-pitched, it was impossible to whistle, and blown-out candles seemed to re-light themselves as if by magic.

Soon, the physical effects of working such environments took a darker turn. Foremen started hearing complaints from workmen experiencing severe stomach, head, and joint pains when they emerged from the stairwell. Others suffered temporary paralysis in legs and arms, causing several to be admitted to a local hospital.

The situation became deadly on March 19, 1870, when a man named James Riley emerged from the center access shaft, informed a friend that he was feeling well, and promptly keeled over. He died fifteen minutes later. A few hours later, James Moran, an Irishman who worked in the east pier caisson, died at City Hospital. Three days later, a 22 year-old German named G.S. Alt died after two weeks of hospitalization. The next day, 27 year-old Henry Krausman and 21 year-old Theodor Baum both expired.

The lack of consistency in visible symptoms was confounding. Nearly every case involved stomach and joint pain, but similarities seemed to end there. While several men died, others experienced full recovery within a few hours. An Irishman named Mike McCoole became ill for the first time after three weeks of caisson work while an American named Hugh Devel collapsed on his very first day. An Irishman named Michael Herwin starting spitting blood while a co-worker named James Galloway was found to have pus in his urine. A 20 year-old German named Hansep Miller was hospitalized for nearly two months. Legs fully paralyzed, Miller had no control of his bowels and required frequent catheterization. Another man, a 30 year-old German named William Saylor worked three months in the west pier with no issue. After being transferred to the east pier, he died shortly after his first shift.

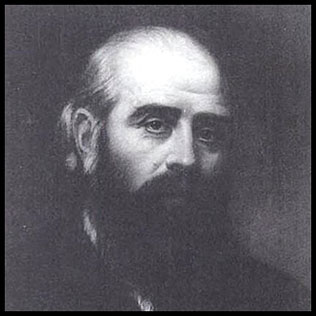

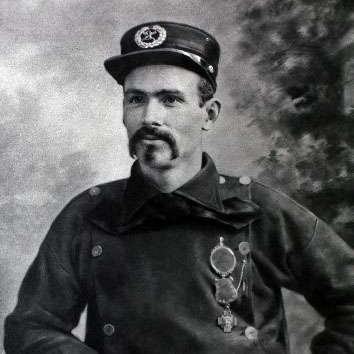

On March 31, Eads assigned his family physician, a man named Alphonse Jaminet, to figure it all out. Already familiar with the problem, Jaminet was the obvious choice for the task. Several weeks earlier, on February 28, 1870, he suffered a near-fatal encounter himself. After spending two hours in the east caisson, Jaminet emerged from the stairwell and discovered that he could barely walk. Racked with pain, he somehow made his way home and spent several hours expecting death to come at any moment. Fortunately it didn’t, and his recovery enabled him to spend the next several weeks doing everything he could to assist those afflicted. His detailed transcript, published in 1871, is the first record in history of what we now know as “decompression sickness”.

Jaminet was faced with quite a dilemma. As John L. Phillips explains in his book The Bends: Compressed Air in the History of Science, Diving, and Engineering, it was unlike anything that had been seen before. It was a disease unique to the Industrial Revolution, and Alphonse Jaminet had no medical or scientific basis to work from.

Named “caisson disease” when it reappeared during the building of the Brooklyn Bridge two years later, it was jokingly referred to as “the bends” by workmen in St. Louis. According to Robert W. Jackson in his book, Rails Across the Mississippi, this epithet evolved from a popular fashion of the time. Men who suffered through the severe stomach and joint pain often walked about with a bent over posture. In the late 1800’s, it looked similar to the “Grecian bend”, a pose many women in Victorian society used to show off their bustles.

Today, we know that decompression sickness happens as a result of leaving a pressurized environment (such as a caisson) too quickly. The increased nitrogen produced in the bloodstream in such an environment requires sufficient time to dissolve when leaving it. If the nitrogen doesn’t dissolve, it may form bubbles in the blood and tissues of the body. These bubbles can lodge in the head, abdomen, or joints, producing symptoms experienced by the men working in the caissons.

Jaminet recorded the details of every case presented to him. He attempted to isolate it by recording each worker’s age, nationality, amount of time worked, their body type, and even their daily behavior. His biggest frustration came from the unruly behavior of the men who paid little heed to his warnings. Mostly Irish and German, many of these men were young, strong, and not the type willing to lay down for a spell. With four dollars of pay in their pocket, many rushed out of the caissons and headed straight for the beer and whiskey offered at saloons and taverns along the riverfront.

Jaminet knew the problem was related to changes in air pressure, but his efforts to remedy the problem never provided the proper level of decompression we know today. Despite this fact, his work must be commended. With the support of James Eads (who also believed frequent saloon visits had a hand in the matter), shift times were reduced, the time between shifts was increased, and men were compelled to rest and eat before going ashore. He even ordered a “floating hospital” built next to the east pier. Many men received overnight care in this facility on the river before being sent home or to the hospital. According to John Phillips, this clinic was the first of its kind to provide on-site care for workers injured on the job.

Perhaps most importantly, he insisted the men working the airlocks, the men essentially controlling the rate of decompression, follow strict guidelines. Prior to this, veteran workers often initiated “greens” to caisson work by opening airlocks as quickly as possible and letting air rush in.

However, a few methods implemented by Jaminet also display the basic lack of understanding of decompression. Along with his belief that drinking alcohol accelerated symptoms, he also believed taking a hot bath would hasten paralysis. Drinking water was forbidden, and men who complained of thirst were given ice cubes or beef tea. He wasn’t alone. Home remedies circled around the workmen themselves, including various elixirs and useless “magneto-electricity” amulets made of silver and copper.

Despite fifteen deaths, two permanently disabled men, over 100 caisson workers severely afflicted (not counting the men who simply walked off the job when they became ill) caisson and pier work didn’t miss a beat. In fact, the only time caisson work cease was when workers attempted to strike for higher pay. Knowing that St. Louis provided no shortage of men looking for work, Eads and the bridge company simply waited them out. After a few days without pay, the men shuffled back into the caissons.

By late May 1870, work at the riverbed was complete. James Eads was filled with pride in observing the two the two largest and deepest bridge piers ever constructed rise out of the water. As Howard Miller explains in his benchmark essay about the bridge, he had ample reasoning to admire his masterpiece. His accomplished marked a new chapter in the annals of civil engineering. In discussing his accomplishment, Eads wrote:

“When I left it to-day, I could not help being impressed with the feeling that I had never undertaken any mechanical or engineering performance before with such full assurance that failure was absolutely impossible as in the case of this, the greatest work of my life…”

This sentiment is remarkable for a man whose life was filled with wondrous accomplishment. That story comes next in the Summer of Eads.

![]()

Selecting a drink to celebrate the Eads Bridge was difficult. I can’t drink on the bridge, and the rows of saloons and taverns that once welcomed caisson workers between shifts are all long gone. But I wanted to find something I could tie to the men who did a job I’d never sign up for.

Despite Jaminet’s warnings about drinking alcohol, one can’t blame these guys for ignoring him completely. As I spend my days sitting in a cubicle for too much money, these guys spent their days shoveling mud for not enough. If they didn’t drink for the taste, they certainly drank to celebrate surviving another shift.

A final anecdote found in my research further illustrate the dangerous changes in air pressure these men experienced. In Rails Across the Mississippi, Robert W. Jackson tells the story of a caisson worker who inadvertently carried a flask of brandy in his pocket down into an air chamber. Or perhaps it was intentional, and this man thought a few nips far below would help prevent the joint pain he suffered after work. Either way, it must have been a shock when he emerged at the surface and the flask exploded in his pocket. If he hadn’t already determined his job was dangerous, he surely must have realized it at that moment.

Personally, I wouldn’t climb down into a caisson if the reincarnation of James Eads came back to life and offered to lead me down into one himself. Instead, I decided to simply go stare at it again, just as I did after my new friend Amanda told me her version of its story.

But this time, I brought a flask of brandy with me. With no risk of it exploding in my hand, I raised it and drank to the men who worked and died building our famous bridge.

Sources invaluable to this post:

- Rails across the Mississippi by Robert W. Jackson, 2001

- The Eads Bridge by Howard Miller and Quinta Scott, 1999

- A History of the St. Louis Bridge by C.M. Woodward, 1881

- The Bends: Compressed air in the History of Science, Diving, and Engineering by John L. Phillips, 1998

- Physical Effects of Compressed Air, and of the Causes of Pathological Symptoms Produced on Man, By Increased Atmospheric Pressure Employed for the Sinking of Piers, in the Construction of the Illinois and St. Louis Bridge over the Mississippi River at St. Louis Missouri by Alphonse Jaminet, M.D., 1871

Props to Amanda Clark for fostering your interest in Eads. I’m left with the image of the Grecian bend and contemplating the mystery of fashion. Damn fashion trends that incapacitate women! and damn those nitrogen bubbles!

You can also pour one out for Eads himself. He’s buried in the Bellfontaine cemetery .

Great job. I am actually learning a lot about the Eads Bridge while currently reading David McCullough’s, “The Great Bridge – The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge,” because it was going up at about the same time. Eads even gave a tour of one of his caissons to the Brooklyn Bridge’s chief engineer, Washington Roebling, and later sued him for stealing a design used in Roebling’s second caisson (which Roebling insisted was ridiculous, but settled out of court anyway). I will read parts II and III of your story later, but first I must finish my book! It will be on my blog in one week, though in many fewer words, I am sure! 🙂

Thanks for reading and commenting! I am familiar with the Roebling-Eads spat. I planned to make it a “Part V” or whatever, but decided to put it off for a later follow-up. Such a great story, Isn’t it?

Great series of posts on a subject I am also fascinated with. A slight correction on the science of what happens in decompression sickness – Blood can and does hold more nitrogen at higher pressures, so in rapid decompression the gas actually comes *out* of solution too rapidly, forming bubbles. It’s like carbonating a drink under pressure and then opening the bottle. Slow decompression allows the nitrogen to “undissolve” at a pace where no bubbles are formed.

Thanks so much. I appreciate the clarification (I try, but I’m not much of a science-y guy). Thanks for reading!

Very nice. Is there a source (S) that lists those who worked on the bridge. I have a great-great grandfather who was a stone mason, from Indiana, who purportedly worked on the bridge. He died in 1870.

Sharing the same name, I have always been captivated by Eads’ accomplishments. I have created models of some of his ironclads (in action months before anyone heard about the Monitor and Merrimac). I am also working on a model now of his planned ship-railway across Mexico. After the bridge, probably his greatest achievement was the construction of the South Pass Jetties, opening up the Mississippi to trade and prosperity unimagined before (all done with his own financial resources).

Your blog is well written and I very much enjoyed the detail you brought (but made entertaining). While he did live on for a couple of decades, his health was decidedly worse after the bridge was completed and probably ended his life prematurely (it was right in the middle of his ship-railway project).

Thank you for your work.