Note: This is part two in a series I have titled “The Summer of Eads”. Dealing with a subject (James B. Eads) that is impossible to fit into a single Distilled History post, I’ve decided to write a few. Part one can be found here.

A couple of weeks ago, I spent some time strolling through the Loop and taking note of the numerous stars and plaques embedded in the sidewalk as part of the notable “St. Louis Walk of Fame” exhibit.

The 137 names on the Walk of Fame, each signified by a brass star and descriptive plaque, stretch for several blocks on each side of Delmar Boulevard. These stars are actually a significant source of nostalgia for me. I don’t get to the Loop much these days, but when I first moved to St. Louis in 1995, I worked in a bookstore just a couple of miles away. The few measly dollars found in my paychecks were usually spent in bars that had one of these stars in front of it.

The Walk of Fame was established in 1988 by Joe Edwards. He’s also the guy behind the famous Blueberry Hill, a bar those stars have led me to more than any other. I’m sure that stopping to read the various plaques while heading into (or stumbling out of) Blueberry Hill is one of the many reasons I became interested in the history of this town.

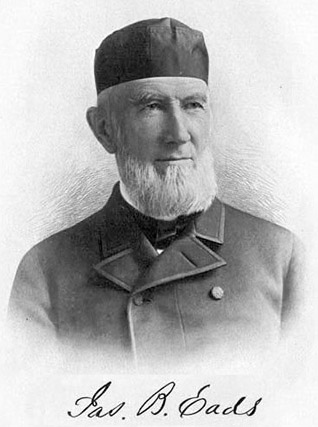

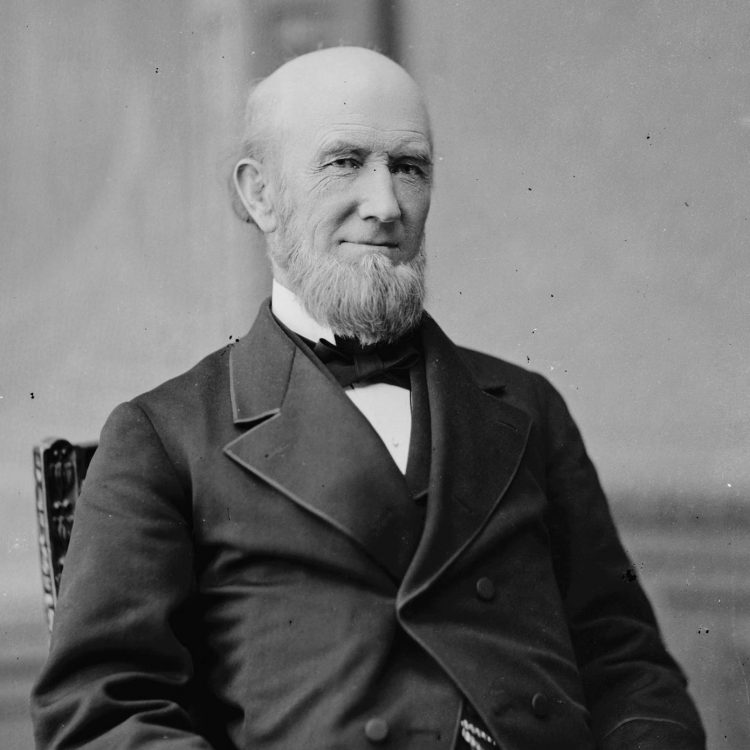

I found the star for the subject of my summer, James B. Eads, outside a tattoo parlor on the north side of Delmar. One of the first names selected for Walk of Fame induction back in 1989, Eads deservedly went in alongside notable St. Louis names such as Chuck Berry and T.S. Eliot.

As I took a long look at his plaque, I thought about how little I knew about the man before I began this project several weeks ago. I think most of St. Louis is in the same boat. We all know his bridge, but the story behind the guy who built it is largely unknown. With that in mind, I thought it would be fun to tell the story of James Eads before he became an internationally renowned engineer. Turns out it’s a darn good story.

Surprisingly, I couldn’t find much about his early life. Plenty of sources provide detail of his engineering prowess, but few provide more than a brief overview of his early years. Many of them rely on one source, a short biography written in 1900 by Louis How, Eads’ own grandson. It may have been fun to find to find some dirt on this guy, but I don’t think there’s any to find. As I gradually learned, James Eads was a indeed a special guy. He had it figured out from the start.

James Buchanan Eads was born on May 23, 1820 in Lawrenceburg, Indiana. He was the youngest of three children to Thomas Clark Eads and Ann Buchanan. Regarding Thomas Eads, Louis How asserts he was never “very prosperous”. So he moved his family to find stable income, first to Cincinnati in 1822 and then to Louisville in 1829. In 1833, Thomas Eads decided to uproot his family again, this time to St. Louis. At the age of thirteen, young James Eads boarded the steamboat Carolton. Along with his mother and two sisters (his father stayed behind to gather supplies for a store he planned to open), James Eads started his journey west, to the city where he’d make his mark.

Traveling on a steamboat was surely a wonder for the young, curious Eads. Fascinated by machinery and mechanics from an early age, his father supported his interest by building James a small workshop in Louisville. Four hours on end, he tinkered away in it, taking apart the family clock, building scale models of steamboats, and even constructing a functional steam engine. As Louis How recounts in his biography, a particularly boyish (and ingenious) moment during this childhood occurred when he produced a small wagon that mysteriously moved about the room. As his mother and sisters gaped in awe, it was soon revealed that the motive power was produced by a live rat hidden underneath.

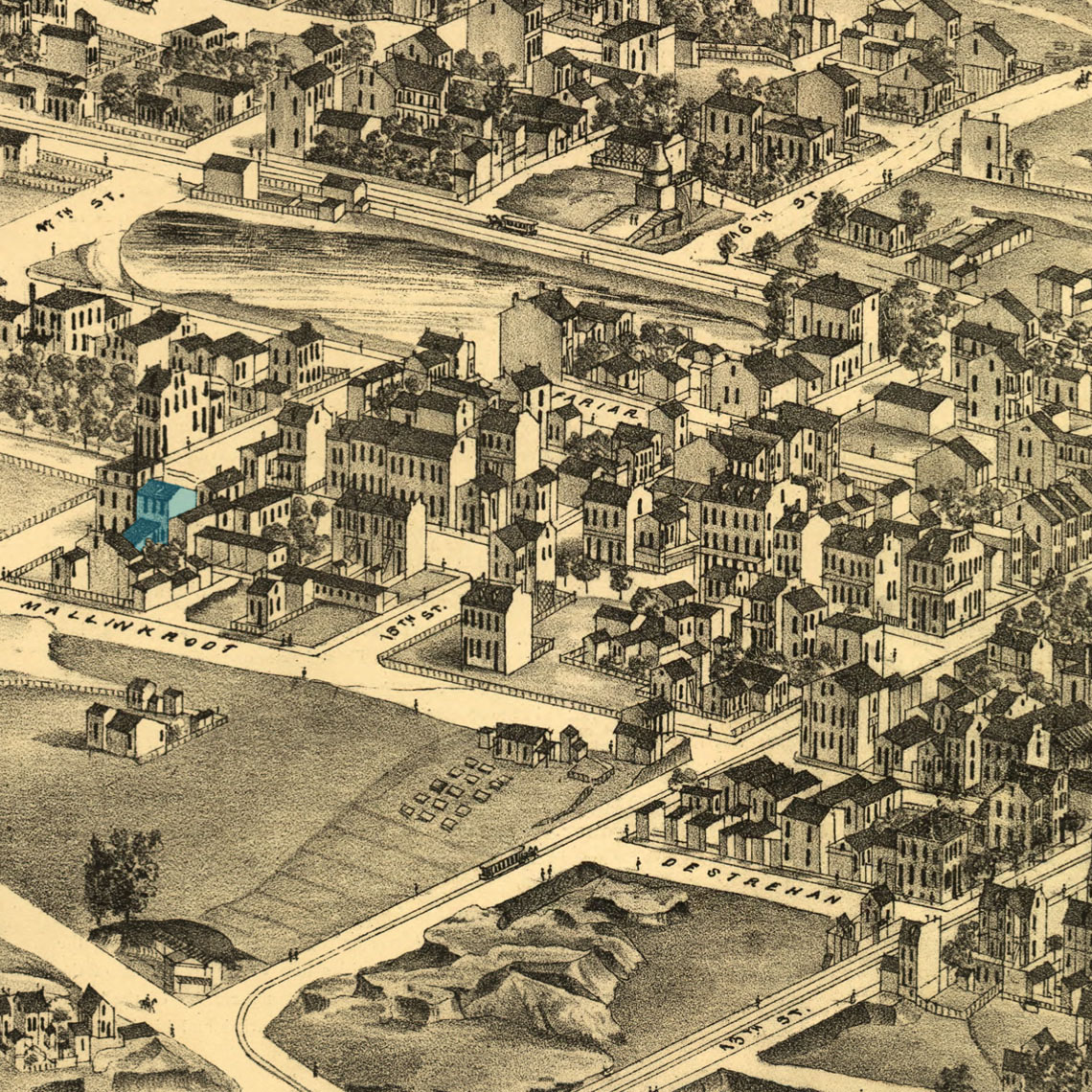

Upon arriving in St. Louis, Eads would need every bit of ingenuity he had. As the Carolton approached the St. Louis riverfront on September 6, 1833, a chimney flue toppled over. A deadly fire broke out, killing eight people and severely injuring many more. Ann Eads and her three children emerged on the riverfront unharmed, but all of their possessions were lost. Save for the clothes on their backs, the Eads family suddenly found themselves alone and penniless in a mysterious new city.

James Eads responded to this adversity with the same hard work and determination that would be indicative of his later career. Discontinuing his formal education in order to help support his family, he started by selling apples on the street. Soon after, he caught the eye of a boarder in a house his mother rented, a mercantile owner named Barret Williams. After recognizing the talent of the young man, Williams offered Eads a job as a clerk in his store, a position that would ultimately provide far more than an income.

It’s during this time when the genius of James Eads really begins to take root. Along with a job, Williams gave James Eads access to his personal library. With no formal schooling past the age of thirteen, it was in this library where James Eads continued his education – on his own.

In the late hours after the mercantile closed, he poured through the classics, became a fan of poetry, read books about science and history, and most significantly, taught himself engineering and mathematics.

Eads began to apply his self-education in 1839, when he took a job as a mud clerk on the steamboat Knickerbocker. His family had moved again, this time to Iowa, but Eads opted to stay back and pursue opportunity in St. Louis. Among other responsibilities, a mud clerk was responsible for wading through the muck, clearing away obstacles, and securing a boat to shore. It was arduous work, but it offered the hands-on riverboat experience he wanted. And most importantly, it’s where he’d start to become fully acquainted with the river that would shape his brilliant career – the Mississippi.

James Eads would come to understand, as much as anyone in his time, the sheer power of the Mississippi. He lived it aboard the Carolton 1833, and he’d live it again when the Knickerbocker was ripped apart by a snag in 1839. For the second time in six years, Eads found himself shivering on shore and watching the boat that just carried him sink to the bottom of the river. But this time, James Eads had an idea.

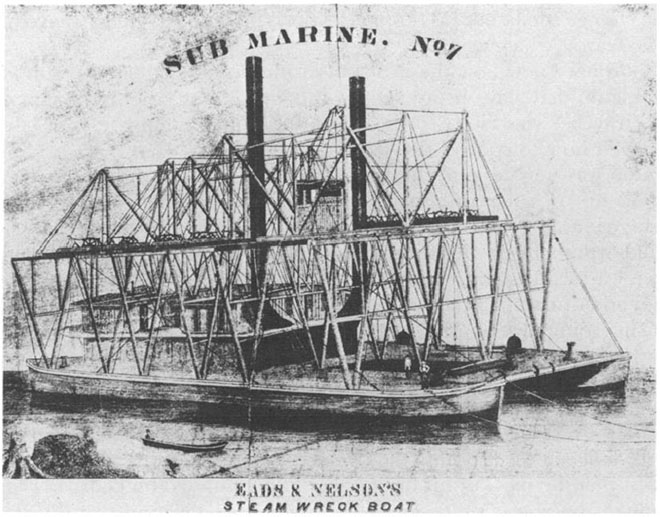

The Mississippi, with its unpredictable currents, heavy sediment movements, and countless snags, sank boats on a daily basis. James Eads realized a profit could be made from the cargo that sank with them. In the 19th century, “wreckers” were paid handsomely by ship owners and insurance companies to salvage valuable materials from sunken boats. Additionally, laws of the time stipulated that anything sitting at the bottom of the river five years after it settled there became the property of anyone who could get it.

But it was extremely dangerous work. Salvage boat and diving technology at that time was rudimentary, causing even the bravest of souls to pass on such work. But James Eads, already confident in his own ability, went to work designing a new salvage vessel of his own. After months of revisions and improvements, Eads presented his design to two St. Louis businessmen. Surely amazed by what the 22-year old had proposed, the two men agreed to provide financial backing. Before long, Salvage Boat No. 1 was under construction. James Eads was about to start the next chapter of his life at the bottom of a river.

The venture was an instant success. His “Sub Marine“ found ample reward as it raced around western rivers raising lost cargo before competitors could get to it. At the same time, Eads invented a diving bell, weighted with lead, rigged to air pumps, and equipped with a small seat inside. Inside and submerged, a wrecker could move around the bottom of the river while withstanding fast river currents.

As brave as he was ingenious, Eads did much of the diving bell work on his own. Henceforth known as “Captain” James Eads since he piloted his own boats and worked alongside his men, Eads displayed a remarkable personal commitment to his work. As Louis How writes, Eads boasted later in life that a stretch of fifty miles didn’t exist between St. Louis and New Orleans in which he hadn’t stood under his diving bell on the riverbed.

This is indicative of the kind of man James Eads was becoming. As he grew into an adult, James Eads developed into a brilliant and profoundly thoughtful man. According to sources, he was inquisitive, generous, and supportive of those close to him. He loved nature, read poetry, and was a very skilled chess player. He enjoyed riddles and humor, but he was tactful and when necessary. Some viewed his confidence as arrogance, but even his detractors considered him an exceptional man.

A successful and respected man by his mid-twenties, Eads now turned his attention to family life. In 1845, he married his cousin, Martha Dillon, after a tenuous courtship (remarkably, Martha’s father didn’t approve of the young inventor). His love for Martha was profound; so much so that he looked to find work closer to home. To do this, he decided to sell his interest in the salvage business and find work where he could stand on solid ground.

The decision would mark the beginning of a difficult chapter in his life. After leasing a large building in St. Louis, Eads invested heavily to transform it into a glass factory. It was the first of its kind west of the Mississippi, but the business struggled from the start. Within two years, sales remained stagnant and his fellow investors pulled out. Suddenly, James Eads found himself with a warehouse full of glass and $25,000 of debt.

To pay off his creditors, James Eads had no choice but return to salvage work. Fortunately, the financial turnaround was immediate, but tragedy continued to darken his personal life. In 1849, James and Martha’s only son James died in infancy. Then in 1852, James Eads lost his mother. In a final devastating blow, he lost his beloved wife just a few months later to cholera.

In a letter to Martha before she died, James Eads wrote “‘Drive on’ is my motto”. Drive on he did, and despite personal adversity, his professional life flourished. The salvage business continued to boom during his absence, and he found no shortage of work when he returned to it. Any remaining financial questions were answered in 1849, when a devastating fire on the St. Louis riverfront sunk over twenty riverboats. Eads was contracted to salvage nearly all of them, and the profits put him over the top for good.

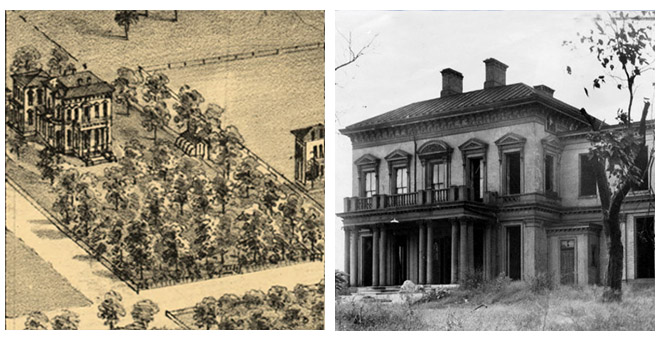

As his wealth multiplied, James Eads also discovered that life at the bottom of a river can catch up to a man. Battling various health issues, he decided to give up diving in 1853. After re-marrying in 1854, he purchased a mansion on Compton Hill just west of Lafayette Square. Then in 1857, with a fortune of $500,000 in the bank (about 12 million in 2014), James Eads retired from salvage work for the last time.

He was just thirty-seven years old. And he was just getting started.

Stay tuned for the Summer of Eads Part III, in which James Eads goes to work for the Union in the American Civil War.

![]()

Once again, I found myself at the end of a post coming up a drink to connect to the life of a subject that died long ago. This seems to happen often with what I call “the biography posts” (other examples include Homer G. Phillips, Elijah P. Lovejoy, and T.S. Eliot). Not able to find a bar or drink that I could connect Eads to, I almost copped out and simply drank from a flask in front of his bridge again.

But at the last-minute, I remembered a great story I read about James Eads when he was first getting started in the salvage business.

It happened in his first year as a wrecker, when his first salvage boat was still under construction. Offered a contract to raise 100 tons from a sunken barge in Iowa, Eads didn’t want to pass on the opportunity. To do the job, he rigged a barge with derricks and hired a Great Lakes diver from Chicago to come down and do the work.

When the diver descended into the river, it became apparent the diver’s armor wasn’t suitable for river work. Used to calmer lake water, the fast Mississippi River currents thrashed the man about on each descent. After several attempts with no success, the frustrated (and likely terrified) diver threatened to quit and head home.

When the diver descended into the river, it became apparent the diver’s armor wasn’t suitable for river work. Used to calmer lake water, the fast Mississippi River currents thrashed the man about on each descent. After several attempts with no success, the frustrated (and likely terrified) diver threatened to quit and head home.

Thinking quickly, Eads had an idea. He rushed into town and purchased a 40-gallon whiskey barrel. Bringing it back to the wrecking barge, he knocked one end out, fastened several pigs of lead to the opening, and connected air horses to the other. He then instructed the diver to get inside and be lowered into the river.

The diver adamantly refused to get inside such a contraption, so Eads was forced to do it himself. Remarkably, the diving bell worked. After several descents, Eads had brought up much of the sunken cargo himself. The diver, realizing the bell was safe and effective, took over and finished the job.

I’d like to think Eads purchased a full whiskey barrel and helped empty it, but that’s probably not the case. But at least I know he bought one. And that’s good enough for me to tie this post to whiskey.

Even better, I was able to purchase my own (much smaller) whiskey barrel at a local liquor store. It’s the perfect size to make a diving bell for my cat, but it’s probably better used in toasting the accomplishments of a great St. Louisan.

To drink a toast to James Eads, I filled it with a bottle of J.J. Neukomm, a hand-crafted single malt whiskey made right here in St. Louis. It’s even aged oak barrels, just like a guy who spent much of his life inside one.

Sources invaluable to this post:

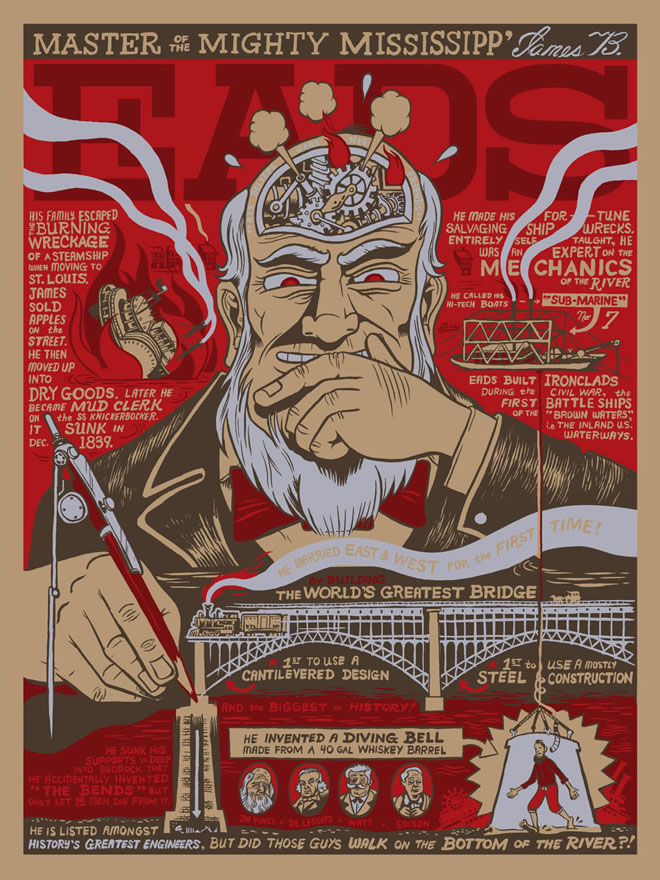

- Zettwoch’s Suitcase – A blog by artist Dan Zettwoch

- Road to the Sea by Florence Dorsey, 1947

- Iowa Journal of History and Politics, Vol. 41 No 1, 1944

- Rails across the Mississippi by Robert W. Jackson, 2001

- The Eads Bridge by Howard Miller and Quinta Scott, 1999

- A History of the St. Louis Bridge by C.M. Woodward, 1881

I must say Eads’ first wife had some beautiful eyes…

Great stuff

This is a story for Drunk History! I live on Eads down the street from Terry Park. I am grateful to be able to learn about the history of my neighborhood and the man for whom my street was named. Thank you!

Glad you enjoyed it. Thanks for reading!

While working as a St.Louis police officer, I met an elderly women who lived in a huge mansion located at the corner of Cabanne and Hamilton Avenues. Her name was Grace Firquin. She claimed to be the former wife of Robert Griesediek who was shunned by tne family after Roberts passing. She also claimed that James Eads lived in the mansion at one time. There was a huge ornately decorated upstairs bedroom which she refered to as the Eads Room. Signifantly. the huge brass plates which surrounded the door knobs in that room only, bore an engraved likeness of the Eads Bridge. This occurred in the early 1970’s. Could this be true???? Thanks.Bob

r

On our way west by car, I happened on your blog series on James Eads. I must say it made an amazing trip for us as we traveled to Marceline to experience Walt Disney’s hometown, another American innovator and national treasure, as was James Eads. Thank you so much!