Here’s a fun Distilled History tidbit. I briefly mention in it the “About” page on this blog, but the first version of Distilled History didn’t have anything to do with history. Initially, this blog was going to tell people how to drink.

No joke. After brainstorming ideas with an old friend, I came up with an idea to write a St. Louis cocktail blog. The plan was to drive around St. Louis, tell some fun stories, and write blog posts about who was making a Manhattan cocktail correctly (by stirring it) and who wasn’t (by shaking it). But after a few preliminary drafts, I realized something was missing. I love drinking, but history is my true passion. Not to mention, the idea of publicly judging (and quite possibly annoying) a large group of people who have been very good to me (St. Louis bartenders), a cocktail review blog didn’t seem like the best of ideas.

So I mixed history and drinking together. And just like that, Red, Clear, or Beer became Distilled History.

I’m glad I made the switch, but seeing the original logo reminded me that Distilled History has never become the drunk I intended it to be. I’ve had great fun with St. Louis brewery histories, cocktail histories, and other drinking-related posts, but I know more alcohol is needed here. So I’m going to take a break from my favorite city (St. Louis) and focus my efforts on my favorite booze. That special spirit is gin, and the historian (and cocktail snob) Bernard DeVoto sums up my sentiments about the stuff pretty well.

Gin is also an ideal topic for this blog because it has a special story behind it. The history of gin includes riots, wars, revolutions, Italian monks, Dutch distillers, English mercenaries, and even a guy nicknamed “the Orange”. There’s an actual era in English history known as “The Gin Craze” in which an entire country took their love for gin WAY too far (and inspired the title of this post). And although many have told gin’s story already, I thought I’d give it a shot. I had fun with it, but what follows is a whirlwind trip. I did my best to hit the major points of gin’s story, but there is much more to it. Gin: A Global History by Lesley Jacobs Solomonson and The Book of Gin by Richard Barnett are both great sources (along with many others) that can fill in the gaping holes I’ve left here.

Before I get to gin itself, I have to provide a little background on gin’s essential ingredient, the juniper berry. Interestingly (and a sign of what’s to come), juniper berries aren’t actually berries. They are seed cones, and people have been adding them to foods and recipes for centuries due to the unique flavor they provide. That’s important to the subject of this post because juniper is what must be present for a distillate to be officially labeled “gin”. That’s right, along with all those gin varieties containing everything from coriander, saffron, rose petals, cinnamon, cucumber, and pine needles, every one of them must also contain juniper if “Gin” is written on the bottle.

Juniper wasn’t always just a flavor, though. As Richard Barnett details in his The Book of Gin, juniper has been lauded since ancient times for its medicinal properties. The ancient Greeks used it to cure tapeworm, the Romans rubbed it under togas as a contraceptive, and medieval Europeans placed juniper twigs in masks to help fend off the plague. Barnett also details a significant twist around the year 1050 when a bunch of monks in Salerno, Italy infused juniper in distilled wine. Their intent was to create a medicinal elixir, and the recipe was recorded in a compilation of tonics titled the Compendium Salerta. This may have been the first time juniper and alcohol came together as one, and Barnett notes this “proto-gin” is the earliest recipe for anything that resembles what we call gin today.

From these Italian monks, we can thank the Dutch and English for gin’s evolution from a juniper-based elixir to what it is today. But before I explain why, I have to mention the process known as distillation. That process, separating components from a liquid through heating and cooling, is how alcohol is separated from fermented materials such as fruit, potatoes, and grain. Unlike beer and wine, which can happen by accident if yeast happens to be floating around, distillation is a necessary step in the production of spirits like gin and whiskey.

Distillation (as we know it today) got its start in the 8th or 9th century when alchemists like Jabir ibn Hayyan were trying to figure out how to turn cheap metal into gold. Slowly (with help from inventions like movable type), the distillation how-to manual worked its way to other parts of the world. By the mid-16th century, stills could be found all over Europe, mostly producing healing concoctions referred to as “aqua vitae” (Latin for “water of life”). But distillation, a process rooted in healing for hundreds of years, began to change when it arrived in Europe’s Low Countries.

That’s where the Dutch, a people with a hearty grain surplus and plenty of flavor creativity, embraced a new trend of recreational drinking. Intent on making elixers that tasted better, Dutch distillers began adding herbs, botanicals, and sweeteners to hide harsh tastes produced by unrefined distillation methods. It worked better than expected, and gradually national-scale industry emerged. By the mid-1600’s drinking spirits for the taste (and the intoxication that went along with it) was all the rage. The signature product was jenever, a juniper-based spirit that is maltier and sweeter than what many know as “gin”. Jenever is also known as “Dutch gin”, “Holland gin”, or even just “Hollands” (it’s also often spelled with a “g”). Today, jenever is the national liquor of the Netherlands and Belgium and remains the most popular spirit in that part of the world.

We should all raise our glasses to the Dutch for getting the juniper-based spirit trend going, but the next major players in the story, the English, should get a toast as well. Dutch jenever made its way to England as early as the 1500’s, but it could barely compete in a country filled with pubs serving pints of ale. But according to most gin historians, two major historical events helped England get into the gin game. As a result, jenever would evolve into distinctly English spirit with a shortened name.

The first was the 30 Years War (1618-1648), a conflict in which the Dutch Republic fought to win its independence from Spain. England sent an army to help the Dutch, and in the hours before going into battle, English soldiers steadied their nerves by drinking cups of jenever supplied by their Dutch allies. This is the origin of the term “Dutch Courage”, and when the Spanish were defeated, a large number of English soldiers returned home with a taste for something new.

The second event was 1688’s Glorious Revolution. That’s when the Dutch Republic’s William of Orange arrived in England to overthrow the unpopular King James II. Parliament invited William and his wife Mary to take the throne, and they became co-monarchs in 1689. Taking a page from their Dutch playbook, William and Mary encouraged grain production to get the English economy going again. One way they did that was to make it easy (really easy) to distill grain-based spirits. The industry was unregulated and untaxed, and suddenly anyone in England who wanted to make or sell gin could do so.

This all sounds pretty great to a present-day gin drinker, but the results were catastrophic. While some distillers adhered to high standards carried over from the Dutch, a new type of gin maker emerged. Using cheap ingredients and near-toxic levels of alcohol, libations known as “scorch-gut” and “mother’s ruin” became common in England’s major cities. Many didn’t even bother with juniper, using poisons such as turpentine and sulfuric acid to hide the taste. This gin industry was also directed entirely towards the urban poor, often manufactured in seedy back-alley gin shops and sold for pennies in grimy drinking dens. Crammed into the dirty back-alleys of cities like London and Bristol, the masses didn’t hesitate in drinking as much of it as they could. Cheaper than ale, gin helped people fend off pangs of hunger and forget about a life of impoverishment. This period, or event, or whatever stretch of Hell it was, is famously known as England’s “Gin Craze”.

The term “Gin Craze” may be a fun title for a 21st-century blog post, but it was anything but in 18th century England. In less than fifty years, consumption of distilled spirits in England’s major cities quadrupled. Debauchery ruled, with crime, murder, and suicide rates spiking while birth rates plummeted. For the first time in history, women drank to excess in public, and it wasn’t uncommon to find drunk children alongside them. In what could be the most notorious example of gin’s treacherous influence, in 1734 a woman named Judith Defour strangled her own daughter and left her body in a ditch. When forced to explain her crime, she reported she needed to sell the child’s clothes so she could afford another serving of gin.

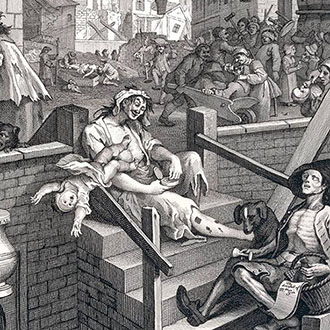

It didn’t take long for many to realize that things were of control. As consumption of spirits increased, so did public outrage. Moralists, politicians, and pretty much anyone with a box to stand on started shouting about the impending collapse of society. Perhaps the most famous example of anti-gin propaganda came in the form of two prints published by William Hogarth in 1750. In “Gin Lane” Hogarth depicts a scene of London debauchery and chaos. Among other images, a baby tumbles from a drunken mother’s lap, a man is seen chewing on a bone along with a dog, and people in the distance are lifted into coffins. On the flip side, “Beer Street” shows London as a happy, productive place. Artists paint, portly people smile with mugs of ale, and everyone productively goes about their day.

Hogarth’s (and other) efforts eventually paid off. Parliament took its first step in 1729 with the first of eight “Gin Acts”. The first few attempts at regulation didn’t go over very well (people rioted) but Parliament continued to tweak the rules by imposing taxes on gin, restricting where gin could be sold, and even rewarding informants who reported gin-related crimes. After the final gin act was implemented in 1751, the gin craze flickered out. New regulations put the back-alley distillers out of business, and the pint of ale slowly regained its place as the preferred English method of getting a buzz.

But the taste for gin never left, and a handful of reputable distillers came to prominence by producing high-quality gins. Many of them are still around today, including Gordon’s (established in 1769), Plymouth (established in 1793), and Tanqueray (established in 1830). Gin sellers also helped improve gin’s reputation by opening classier, upscale bars known as “gin palaces”. These venues, which became popular in the 1830’s, offered a safe, well-lit (often sparkly), and sophisticated venue for one to enjoy a glass of gin.

Improvements to the distillation process also helped. The invention of the column still (also known as the Coffey still) in the mid-1800’s enabled distillers to efficiently (and continually) produce a spirit with more alcohol and subtler flavors. As a result, a style of gin unique to the English emerged. Less reliant on sweeteners and bold flavors commonly found in Dutch jenever (which is made in a pot still), “London dry” gin has since grown to become the most popular style of gin in the world.

With the Dutch and English settled into their own corners of the gin world, it’s time to bring this post to a close. There’s much more to the story (so much that it makes my head hurt), but what comes next is just too much to get into. It includes other gin varieties (such as Old Tom gin), gin’s path to America, gin during Prohibition, and the stories behind all of the wonderful gin cocktails. I’ll get to those stories in due time, it’s time to get back to St. Louis history (and ordering a much-needed) gin-based drink.

Where to get my drink to celebrate gin was a no-brainer. Few places are as dear to my heart as The Gin Room, located at 3200 South Grand in St. Louis. It’s a gin-lover’s paradise, with shelves packed with countless styles and variations of gin reaching all the way to the ceiling. I also love the place for the events that are always happening there, including gin tastings, tonic workshops, and random gin celebrations.

Best of all, the people at the Gin Room (led by my pal and owner Natasha Bahrami) know their gin. One of the few places where I get overwhelmed by the cocktail menu (a rarity), I always end up with a great recommendation at the Gin Room. The result of my latest visit was no exception, when I was served a Fillier’s martini to close out this celebration of my favorite spirit.

I’ll be back to the Gin Room (I’m even house-hunting near it), so the days ahead are sure to be filled with aqua vitae. My own gin craze will continue for years go come.

Thank you. I hardly ever drink beverages that contain alcohol, but I began buying gin to make the raisin and gin arthritis remedy. Juniper berries is said to be the necessary ingredient, yet the labels of most brands have wording something like, “made with the finest botanicals.” I wonder why they doesn’t just say “juniper berries.” https://www.peoplespharmacy.com/2014/10/23/how-to-make-gin-soaked-raisins-for-joint-pain/

In the late 70’s I graduated from the Tom Collins to Gin & Tonic with a twist of lime. I have remained faithful to the later ever since. I enjoyed your post very much. I look forward to the rest of the story………

I graduated from the beer to the gin and tonic. It is now my “go-to”. Thanks for reading! And yeah, I’ll get to the rest of the story as soon as I can. It was so tough to stop, but the post was getting soooo long.

Cameron, not related to this article, I was hoping to talk to you about your writing in 2013 about Hop Alley. Got a project going.

Hi Peter, shoot me an email at cameron@distilledhistory.com. I’d be happy to talk with you.