Several years ago, I took part in a bike tour of north St. Louis and learned about a tragic event known as the “Hyde Park Riot”. As the story was told, on a hot summer day in 1863, a bunch of Union soldiers got really drunk and turned a day in the park into a day of murder and mayhem. The mob ripped down an entire bar, fired on a crowd of civilians, and several people were killed. I’ve bumped into this story a few times since (including in my (Almost) Civil War Bike Tour of St. Louis post), but I’ve always wanted to know more.

Several years ago, I took part in a bike tour of north St. Louis and learned about a tragic event known as the “Hyde Park Riot”. As the story was told, on a hot summer day in 1863, a bunch of Union soldiers got really drunk and turned a day in the park into a day of murder and mayhem. The mob ripped down an entire bar, fired on a crowd of civilians, and several people were killed. I’ve bumped into this story a few times since (including in my (Almost) Civil War Bike Tour of St. Louis post), but I’ve always wanted to know more.

I love starting from (almost) nothing when researching stuff like this because I always pick up great history about other stuff. In this case it’s Hyde Park, a St. Louis neighborhood that has always intrigued me. When I drive around St. Louis to look at old stuff, I always seem to end up there. It’s most recognizable structure today is Most Holy Trinity Church, but Hyde Park also has a William B. Ittner School (Henry Clay), one of the St. Louis Carnegie library buildings, and was home to the Hyde Park Brewery until the late 1950’s. It was also home to the Nord St. Louis Turnverein, which was demolished in 2011. There’s much more to Hyde Park, but that’s a pretty good start.

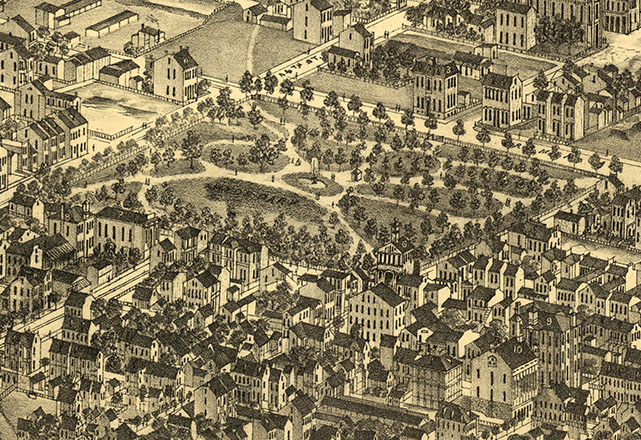

Hyde Park is also the name of a municipal park located in the neighborhood. The park and subdivision were originally part of a large tract of land granted to Gabriel Cerre, which was later purchased by the prominent physician Bernard G. Farrar, the first American to practice medicine west of the Mississippi River. By the 1840’s, the area become known for its large German population (which it retained well into the 20th century). In 1844, four men incorporated the settlement as the town of New Bremen, named after the city in Germany where many of its settlers originated. Today, many may recognize the name of one of those men, Emil Mallinckrodt. In 1867, three of Mallinckrodt’s sons formed the G. Mallinckrodt & Company in Hyde Park. Today, the pharmaceutical giant is headquartered in England, but the company’s U.S. headquarters are still located in St. Louis.

After Benjamin Farrar died in 1849 (he died during the 1849 cholera epidemic), his widow began selling off tracts of the family’s large estate. Named after the famous park in London, St. Louis purchased the subdivision (and park) and absorbed it into the city. St. Louis historian NiNi Harris has noted that the purchase of Hyde Park marked the first time St. Louis paid for parkland. Previously, parks had been created out of land donated to the city or just simply carved out of existing common fields.

The city raised funds to pay for park improvements by renting out the land and existing structures. The Farrar’s old house was converted into a hotel, and a tavern and beer garden were established. The park became a popular venue for political gatherings and related events, especially during the Civil War. On July 4, 1863, Hyde Park was the site of an Independence Day celebration, including music, fireworks, and the launching of a hot air balloon. At the center of it all was a man named Kuhlage, the operator of Hyde Park’s drinking establishment. He went to great effort to get his establishment ready for the day, and “multitudes flocked to the place”. It was reported that as many as 10,000 people came to Hyde Park on that hot summer day, and among them were more than one hundred Union soldiers stationed at nearby Benton Barracks.

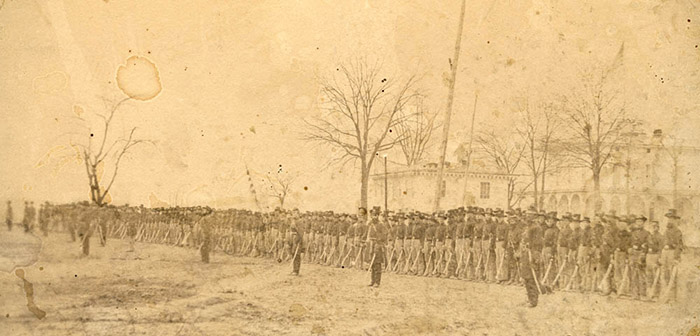

Built on the city’s fair grounds (now the site of Fairground Park at the corner of Grand and Natural Bridge). Benton Barracks was a Union Army military encampment established at the war’s outset. Primarily used as a training facility, the 150-acre complex contained numerous warehouses and barracks along with a 300-bed hospital and a flat terrain perfect for drilling soldiers. Notably, many of of the men stationed at Benton Barracks that summer were soldiers on parole. With not much to do while waiting to be returned to active duty, many visited Hyde Park and its beer garden when given a day’s furlough.

And on July 4, 1863, it seems that’s how the trouble began.

With one side celebrating independence and the other side seeking it, St. Louis must have been a city on edge that summer. Although the Union had a firm grip on the city, Missouri was a slave state and St. Louis was filled with more than its fair share of Confederate supporters. Conflict between the sides had been present in the city since the war began, notably with the Camp Jackson Affair two years prior, a clash between soldiers and civilians that left more than two dozen dead. And with Union soldiers perhaps emboldened by Lee’s recent defeat at Gettysburg and the impending fall of Vicksburg, newspapers reported that the violence that unfolded in Hyde Park that day wasn’t entirely unexpected.

According to the Missouri Democrat, Hyde Park’s Independence Day meltdown began as a conflict between the tavern owner Kuhlage and a number of Union soldiers. The article states that a considerable number of soldiers had already developed an “inimical” feeling towards towards Kuhlage, believing him to be a secessionist. Kuhlage reportedly wouldn’t raise the national flag unless told to do so, and Kuhlage was increasingly frustrated by soldiers drinking their fill and refusing to pay. Accounts in another newspaper, the Missouri Republican, reported that many soldiers confronted civilians in the park, demanding they remove black hatbands and other items believed to be symbols of Confederate support.

The celebration went smoothly until mid-afternoon, when the liquor and beer that had flowed unchecked from Kuhlage’s taps began to take effect. A few scuffles and altercations broke out, but everything was contained until a bartender and a soldier became entangled in a “violent quarrel”. The fight apparently broke out over a drink order; a soldier paid for a drink and wasn’t given the correct change or his order wasn’t filled due to the crowd’s increasing drunkenness. Either way, witnesses stated the bartender produced a knife and slashed soldier’s arm.

Alerted to the altercation, Kuhlage immediately halted all liquor sales, which only provoked the mob further. Riled and inebriated, soldiers began hurling bottles and breaking furniture. Charles Allen, the Provost Marshall of St. Louis, arrived at the saloon and found soldiers outside hurling sticks and rocks through the windows. He noted soldiers and civilians emerging from the bar injured and “bloodied about the head”. The cellar door was open, and several people were seen helping themselves to the food, cigars, and liquor stored within. Two men even carried out a tub of cherries, which a group helped themselves to until Allen tipped the tub over and ordered everyone to cease what they were doing. Seeing another pair walking off with a demijohn (a large bottle) of liquor, Allen was clubbed repeatedly and as he forcefully grabbed it from them.

Outside the saloon, chaos ensued as hundreds began running for the exits. At the same time, Allen rushed to recruit several (sober) soldiers stationed at park gates to help get the situation under control. The men succeeded, and before long the crowd settled down and a band resumed playing. However, many took the opportunity to flee the park for good, including Kuhlage and his cohorts. Although Kuhlage was able to leave the park without injury, he left his house, saloon, and its contents under little or no protection.

While peace had been restored, it didn’t last long. By 5 p.m., the highly-anticipated (and much delayed) balloon ascension had the mob riled up again. As men tended to patching and filling the balloon, drunken soldiers began heckling and jeering their failed efforts. Finally, the mob grew tired of waiting and rushed the partly-filled balloon, setting it on fire. Next, they turned their attention to the large stack of fireworks sitting nearby. In what must have been an impressive pyrotechnic display, the entire cache was lit at once. Finally, with the balloon and fireworks sufficiently destroyed, the mob returned its fury to Kuhlage’s house, intent on destroying what was left of it.

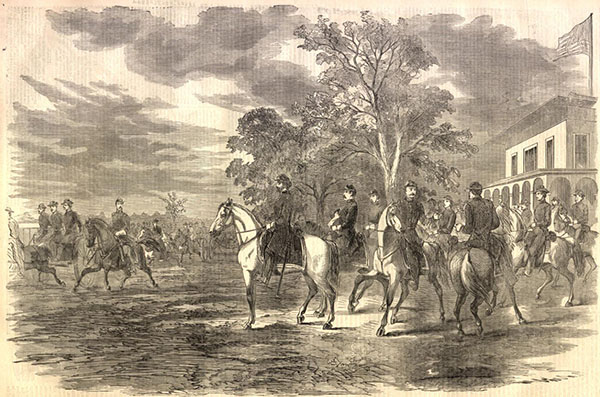

While his saloon was being pulled apart piece by piece, Kuhlage had made his way to nearby Fort No. 10 and asked for assistance. Located just a few blocks away, fifteen to twenty men from the 2nd Missouri Artillery soon arrived on the scene. Under the command of Captain Frederick Lauman, the men lined up in formation and charged into the crowd. The crowd, containing many women, children, and ordinary civilians, broke and ran. The soldiers responded by opening fire. While some witnesses reported the soldiers were instructed to load blanks into their muskets, the bloody aftermath proved that several hadn’t.

When the dust settled, two civilians and four off-duty soldiers were killed. Several others were seriously injured, including a seventeen year-old who had his leg broken by a bullet. An elderly man was beaten by the butt of a musket and slashed three times by a bayonet. Tragically, the two civilians killed were both sixteen year-old boys. One of them was Henry Nieters, who attended the celebration that day with a friend. According to the Missouri Democrat, the friend urged Nieters to leave the park with him, but Nieters responed “Let’s go see what is the matter!” Moments later, Nieters was struck by a ball in the forehead and died instantly.

Of particular interest in the aftermath’s investigation was the fate of John M. Smith, a nurse at Benton Barracks. As Smith walked past a drunken soldier described as “looking for who he should shoot next”, the soldier spun around and fired his weapon directly into Smith’s back. Any notion of soldiers firing blank cartridges quickly disappeared as blood poured from Smith’s chest. One witness reported that after Smith fell, the soldier walked up and said to him in German “Served you right, damn you”.

The chaos even extended into the next day. Although newspaper accounts suggest the situation eased as night fell, looters made their way back into the park by 6 a.m. the next morning. As some resumed breaking apart whatever structures were left, others opened lager casks and rolled barrels of whiskey away. Fortunately, Provost Marshall Allen’s force of twenty-five soldiers arrived to take possession of the park. As the men rounded everyone up and evicted them from the park, the tragic event finally came to an end.

Surprisingly, the tragedy of the Hyde Park riot didn’t get extensive coverage in newspapers. The Missouri Republican reported on the St. Louis Coroner’s inquiry into J.M. Smith’s death for several days, and an editorial castigated city leaders for allowing “licensed drunkerries” to exist in a city park, but little else followed. It may have been overlooked in the limited time allowed to research this post, but the fate of the soldiers who fired on innocent civilians remains elusive. However, the city did take action by banning alcohol sales in the park and it stopped leasing the park’s land out. Perhaps during a conflict such as the Civil War, which produced death and destruction on an almost daily basis, the Hyde Park riot was just another day.

![]()

A big part of my interest in Hyde Park has also been the neighborhood’s once-famous brewery. Located at 3607 North Florissant Avenue nearly a century. The brewery began way back in 1862 as the Hecker Brewery, and became known as the Hyde Park Brewery in 1878. It continued as an operating brewery until 1957 (minus the dark years of Prohibition).

Readers may know that Stag, a beer currently owned by Pabst, was originally a St. Louis-area product. Originally brewed in Belleville, Illinois, Stag was later brewed in Hyde Park. I couldn’t find Stag in Hyde Park when I went looking for it (actually, I couldn’t even find a bar), but there’s a bar on North Broadway named Gregg’s that serves it. Gregg’s sits just outside Hyde Park’s neighborhood boundaries, but I think it’s close enough. And on a sweltering St. Louis summer day, Hyde Park’s former product definitely hit the spot.

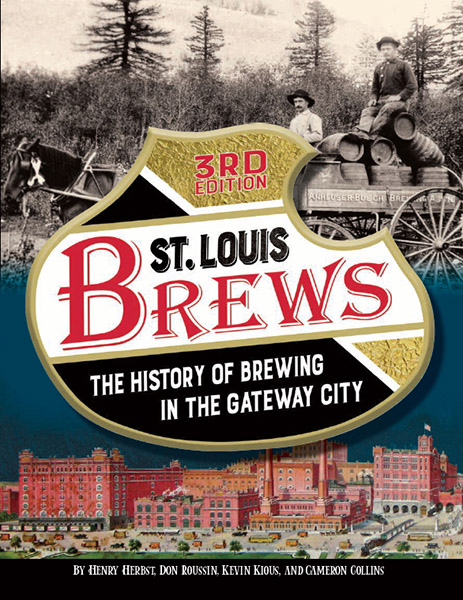

Want to know more about how Stag ended up in Hyde Park? It’s detailed in St. Louis Brews: A History of Brewing in the Gateway City, which will be published on July 31, 2018. In this updated and expanded third edition, the full story of St. Louis’s rich brewing history told. For a limited time, use coupon code STLBEER20 to get 20% off pre-orders placed on this site. I’ll have plenty more to share from this fun project in the near future.

great article, as usual.

Fascinating account! I thoroughly enjoyed this. I know it was a touchey climate during the Civil War here, but little has been revealed about it. Thanks!

Great read – thanks so much for posting. How was the Stag? It’s been over 30 years since I last had one.

Delicious on a hot day! You gotta have one again.

I highly recommend Sullivan’s in Belleville. Best draft Stag I’ve had.

Thanks for the research!

Hmm, booze aplenty and easy access to guns adding up to murder and mayhem. Who would’ve thought?

Enjoyed your article as I grew up in the Hyde Park area. Went there many’s time as a kid and later as an adult. Thank you for your research and sharing with us Northsiders.

Thanks for the nice comment!

I grew up in the Hyde Park area on 20th street. The old brewery was turned into a fitness club and had a banquet hall and a rathskeller in the basement. My oldest sister had her wedding reception there in 1959. Thank you for the memories!! Don Loberg

Thank you! Don, I’m curious how you found this. I’m seeing this post getting lots of traffic lately.

Hi Cameron I just found this post and it was very interesting. I loved reading about it. I recently found a photo that my father left behind. It was about a family bar in Hyde park around this era of time. I was wondering if you had any advice on trying to find out some history about it.

Thanks Jim

Your blog is a true gem in the world of online content. I’m continually impressed by the depth of your research and the clarity of your writing. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with us.

I’ve been following your blog for quite some time now, and I’m continually impressed by the quality of your content. Your ability to blend information with entertainment is truly commendable.