I played an interesting game with several St. Louis friends over the past couple of weeks. I asked about thirty of them a basic history question about our city. Most of the people I quizzed are native to the area, but I also asked a few people (like myself) who came to this city later in life. Either way, I was surprised to discover that very few people could correctly answer this basic question:

After whom is the city of St. Louis, Missouri named?

The simple (and smart-ass) answer to that question is obviously “Saint Louis”. But I wasn’t letting anyone off that easy. “The guy on the horse in front of the Art Museum” didn’t cut it, either. The Louis I wanted to know about was canonized as “Saint Louis” twenty-seven years after his death. I wanted to find out if people knew who, what, and where the namesake of our city was before that.

The idea for this post came from a book I recently read titled Founding St. Louis: First City of the New West by Frederick Fausz. In his book, Fausz vents his frustration over the fact that much of St. Louis history prior to Lewis and Clark is significantly overlooked. It started me thinking about St. Louis history prior to the Louisiana Purchase, and I think I agree with him. We don’t hear much about the periods St. Louis spent as a French and Spanish colony.

Don’t get me wrong, Lewis and Clark and their remarkable journey are a big deal. But St. Louis was founded forty years before they set foot on this side of the Mississippi River. The two men who actually founded the city, Pierre Laclède and Auguste Chouteau, are well-known, but it could be argued they deserve even more recognition. They have some streets, buildings, and businesses named for them, but St. Louisans today don’t even pronounce their names correctly (Pierre and Auguste wouldn’t answer to “Lacleed” and “Showtoe”).

I’ll revisit Pierre and Auguste in a future post since it is a vast and fascinating story. For now, its back to quizzing people Saint Louis. Some of my responders were able to tell me Saint Louis was a king. A few were able to correctly tell me he was a king of France. Others suggested Louis was a “religious figure of some sort” (which isn’t a bad guess). Three people tried to get specific and guessed the French king Louis XIV. Another guessed Louis XVI. About ten people didn’t didn’t even hesitate to admit they had no idea who Saint Louis was.

This, my dear friends, is how Distilled History blog posts come about.

Only two people were able to tell me the correct answer. In April, 1764, Pierre Laclède travelled to the site he and his stepson August Chouteau had recently selected for a new trading outpost. He announced the new village under construction was to be named “Saint Louis”. He named it after the legendary French king Louis IX, but it’s even a bit more complicated than that. Laclède named it after Louis IX and in honor of Louis XV, the current French king (for those keeping count, that makes four different French kings named Louis mentioned in this blog post).

Louis IX was as well-known to 18th century French colonials as George Washington is to 21st century Americans. To this day, he is the only French king to have been canonized (thus the name “St. Louis” instead of something like “Louisville”, which was used to honor Louis XVI in the neighboring state of Kentucky). Laclède’s choice wouldn’t have surprised anyone in 1764. At the time, Louis IX was widely regarded as a model ruler and was considered one of the greatest monarchs in French history. Most significantly, Louis IX was revered as the most religiously devout king in French history.

I did quite a bit of research for this post, and I couldn’t find much to disparage the character of Louis IX. He was a good husband. He was generous to the poor and needy. He was a patron of the arts. He founded a theology college that would eventually become the Sorbonne. He railed against government corruption. He promoted peace in Europe. According to his closest advisor and confidant, Jean de Joinville, the man didn’t even swear. And throughout his reign, France was the most prosperous country in all of Europe. Add it all up and you get a Middle Ages rarity: An absolute monarch universally adored by his subjects.

He did have one fatal flaw, though. Although it’d be considered a magnificent character trait in the 13th century, Louis IX was obsessed with crusading. He believed that his purpose on Earth was to rid the Holy Land from the evil scourge of heathens and infidels that infested it. Despite the few crazies around today who still think this may be a good idea, it isn’t. Louis IX was not tolerant of anyone who didn’t subscribe to his faith. That fact would ultimately bring him down.

As part of my research for this post, I sat down and read an eight-hundred page biography titled Saint Louis by Jacques LeGoff. Although I adore biographies about historical figures, this one was tough to get through. Biographies are better with a bit of drama and scandal. Saint Louis and his pious ways certainly didn’t provide much of that. In fact, It’s a safe bet that Louis and I wouldn’t get along very well if we hung out. I drink too much, I swear too much, and I’m certainly no Catholic. I haven’t stepped into a church for a reason other than a wedding or funeral in twenty years. Louis would probably consider me one of the heathen infidels he was obsessed with booting from Jerusalem. I also take the Lord’s name in vain several times a day, so I’m sure I’d find myself uniquely punished. In the late 13th century, Louis IX demanded that blasphemers get branded on the lips.

Differences aside, Louis IX lived a fascinating life. He was born on April 25, 1214 in Poissy, just north of Paris. His father, King Louis VIII, died when he was only twelve. Crowned at a young age, his mother Blanche of Castille would act as regent until he was of age to rule on his own. It was Blanche that instilled in the young king that he live his life as a devout “Lieutenant of God on Earth”. Her efforts took root. Louis IX developed into a pious and devout ruler. He surrounded himself with Catholic doctrine. He routinely heard sermons and attended mass twice a day. He wore hair shirts and surrounded himself with chanting priests. Most importantly, he pined for the opportunity to crusade and free the Holy Land.

Louis IX announced his long-cherished intention of taking the cross in 1244. After four years of preparation, he left Paris with an army on 1248. The immediate objective was Egypt, led by Sultan Melek Selah. When Louis and his forces arrived there, success was immediate. Louis IX’s forces easily took the city of Damietta, located at the mouth of a Nile tributary.

The good fortune didn’t last long. The summer heat and rising Nile waters prevented Louis from following up on his victory. His army became bogged down and were routed by the Saracens at the battle of Mansourah. As a result, Louis and much of his army were captured. Louis was thrown in prison, and a staggering sum of gold was required to procure his release. Sources say it took two full days to count the gold paid in order to free him.

Louis eventually made it back to Paris, But he was severely humiliated by his failure. In the wake of his defeat, he even considered stepping down as king and becoming a monk. Instead, he focused on eliminating sin in his realm. He started eating and dressing simpler. He also began to work for peace on the international stage, settling long-standing territory disputes with England and other realms. These actions enhanced his image at home and abroad.

But it didn’t help Louis deal with his internal struggle. He continued to believe his purpose for living was to free the Holy Land from the grasp of the Saracens. Despite pleas from his advisors and subjects (his confidant Jean de Joinville flat out refused to go on a second crusade), Louis again announced in 1267 that he would take up the cross. With far less support this time around, Louis left for the Holy Land in 1270.

The result was a disaster. Along the way, he made a rash decision to alter his plans and sail for Tunisia. He had learned the Emir was ready to convert to Christianity and join the Crusade. Upon arrival, Louis learned the rumor about the Emir was false. While camped in Tunisia waiting for reinforcements to arrive, disease broke out in camp. Louis was stricken with dysentery and died on August 25, 1270.

In the years following his death, the legacy of Louis IX grew to a cult-like status. He was widely praised throughout all of Europe and especially in his kingdom of France. Considered “the most Christian King”, the process to have him sainted began almost immediately. He was canonized as “Saint Louis” by Pope Boniface VIII in 1297, just twenty-seven years after his death.

His legacy would last for centuries and spread around the world. It isn’t just St. Louis, Missouri that is named after Louis IX. He’s the main reason nine more French kings named Louis followed him. Other cities named after him are scattered around the globe in places like Mexico, Brazil, Senegal, Canada, Michigan, and obviously, Europe. Along with cities, it would be a daunting task to count the number of cathedrals, churches, missions, lakes, hospitals, bridges, and streets that use his name today.

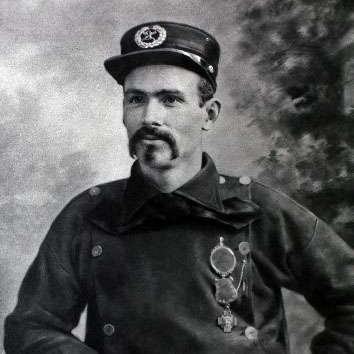

In St. Louis, Missouri, it’s likely that people look upon tributes to him even when they don’t know it. In Forest Park, the Apotheosis of St. Louis in front of the Art Museum is perhaps the most well-known statue in the city. This image of Saint Louis on horseback was actually the de facto symbol of the city until they built the big shiny thing on the riverfront. It may also surprise some that the “Old Cathedral” near the Gateway Arch is in fact named after Louis IX (the official name is the “Basilica of St. Louis, King of France”). The image of St. Louis also used to be on the St. Louis flag, but Theodore Sizer took it off when he redesigned the flag in 1964 (and he was right to do so, as I detailed in this blog post).

Even history buffs who write blog posts about the man stumble upon hidden tributes. Just yesterday, I was driving down Olive Boulevard and noticed a small statue of him in a median near St. Louis University. I was stunned. I had driven or bicycled by that location hundreds of times and never noticed it.

![]()

Since Louis IX died long before the discovery of the new world, he wasn’t even aware of the hemisphere where I was attempting to find a drink in which to honor him. At first, this seems like an easy post to tie a drink to. I could simply go anywhere in the city of St. Louis and claim it was sufficient.

Since I wouldn’t let the people I quizzed about St. Louis off easy, I couldn’t let myself off easy, either. I decided to find a French restaurant at which I could order a true French cocktail in honor of King Louis IX. Located in the Central West End, Brasserie by Niche is an excellent place to fulfill that requirement. I know the place well, and I can also report the fine people behind the bar at Brasserie know how to make a great Manhattan.

Interestingly, the French seem to have an affinity for this location. Prior to housing Brasserie, it was the home of Chez Leon, a wonderful restaurant that has since moved on to well, I don’t know where. I know Chez Leon well because it’s the place where I once watched my father mercilessly berate a server for no sufficient reason. St. Louis severs may owe a small debt of gratitude to my late father for that horrific display. Since that evening over five years ago, I don’t think I’ve tipped less than twenty percent since… even if they shake my Manhattan.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to worry about that at Brasserie. The server (I didn’t get his name) who made my drinks was knowledgeable and helpful. I didn’t know much about purely French cocktails, but the bartender gave me some good suggestions. I started with an offshoot of the French 75 (which I was familiar with) called the Orchard 75. It’s Calvados Brandy, lemon, simple syrup, and champagne served in a champagne flute. It’s a delicious cocktail, and one to come back for when the weather warms up. It is exceptionally refreshing.

The next drink is the one I ordered for Louis, though. While weighing my options, I was told the Parisian is the one cocktail on Brasserie’s menu that is there to stay. It’s been there since the day the place opened, and it’s been on every iteration of the menu since. St. Louis isn’t going anywhere either, so this one is a good fit. The Parisian contains champagne and two aperitifs, Lillet Blanc and Aperol. It was also delicious and I’m happy to have selected Brasserie for my homage to Louis IX.

This is a good thing, because I have some drinking to do for Pierre and Auguste in the very near future.

You read the 800-page books, so I don’t have to. Thanks.

You allude to his intollerance. More specifically he was quoted as saying “The only way to argue with a Jew is to run a sword through him”. Also when the Pope called for the burining of Jwish books through Europe he was the only Monarch who did it. Whne ever I see names like “St. Louis Jewish Light” or “Federation” I realize how paradoxical these names are-sort of like having the “Adloph Hitler Jewish Newspaper”

Great points. I had a small section about his intolerance of the Jewish faith as well, but it was edited out. Now I wish I had left it in. Thanks for commenting!

It should be noted that St. Louis may very well have been doped into believing lies about jews and his actions make much more sense given the context of the Disputation of Paris. A character by the name of Nicholas Donin claimed the Jewish Talmud at the time had blasphemies against Christianity in it. Donin may very well have had an axe to grind since he had been excommunicated by a rabbi and later become a Franciscan. Then he claimed that the Talmud contained horrible things about Jesus and Mary, got the pope involved and then things descended into a debate between Donin and four rabbis, who themselves considered Donin’s translation of the Talmud to a non-Jewish language offensive. After all this the pope declared the Talmud to be burned, probably due to Donin’s arguments and authority as a Franciscan. Remember it’s highly unlikely either Louis or the pope knew how to read the Jewish language, so they only had Donin to go on. Thinking the Talmud was leading Jews away from God (and the Old testament for that matter), Talmud’s were burned in France after Louis followed the pope’s command to burn them. While I don’t think this exonerates Louis of all wrong doing, he wasn’t going around burning Jewish texts because it was fun, but because he thought they were leading Jews estray from their faith in God, something Louis took very seriously. Given this context, Louis comments about Jews make much more sense given what we know about the rest of his life.

When I saw the question I immediately thought “Louis IX” although I am still trying to remember why I know that piece of trivia – especially as a non-native. The best I can recollect is that it had something to do with a prank involving the disappearance of his sword from his statue in FP – not that I was the culprit or anything…

The sword was taken? I have never heard that story! Ha. I’ll never run out of stuff to look into. Thanks for commenting!

the sword has been stolen enough times that they finally welded it into his hand.

heeheehee

Just found your awesome blog. I have an OLD children’s book called A BOY FOR A MAN’S JOB about Laclede and Chouteau’s journey and plans for building StL. Chouteau was the builder at age 13 after Laclede’s foot was broken at Fort Kaskaskia. Anyway, I loved the story so much, and being part French, named my son Auguste in honor of our heritage and StL hometown roots. He adores his historically significant name. Let me know if you’d like a photo of this book. Tara Garcia

I’d love to read that book!