As much as I love the rich history of St. Louis, I must admit that a vivid imagination is often necessary to enjoy much of it. This city has always had an inclination for knocking down old stuff, and that fact makes it tough for many in St. Louis to recall what the streets, buildings, and people who moved among them looked like years ago.

Fortunately, I believe I’ve always had a pretty good ability to think things up. As much as I wish I could still gaze upon long-lost treasures such as the Planter’s House Hotel or Chouteau’s Mansion, I’ve never had a difficult time staring at a parking garage and imagining a vivid St. Louis street scene that occurred there 150 years ago.

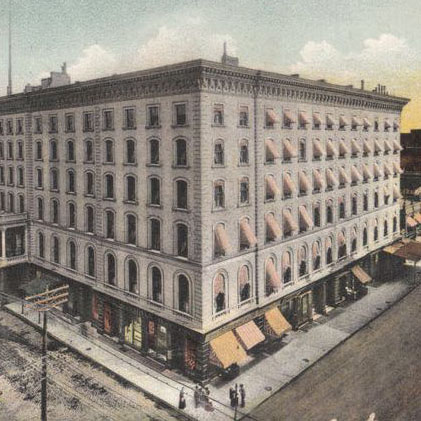

And that’s what I did just a few weeks ago. I hopped on my bike, rode downtown, and worked my way to the corner of 4th and Walnut. That’s where the Stadium East Parking Garage stands today. It’s an active garage, often filled with cars and surrounded by ticket scalpers on Cardinal game days. But as I sat there and stared, I saw something completely different. I was looking at the majestic Southern Hotel, and I envisioned it dominating a bustling corner filled with people, horse-drawn carriages, street vendors, and noise.

Before I go into detail about that vivid scene, I should mention that one could spend days thinking about what’s happened on that corner. First of all, it’s where Fort San Carlos once stood, the centerpiece of the only battle fought west of the Mississippi River during the American Revolution (an event I wrote about in this blog back in 2013).

It’s also where many believe the famous Odowan Indian Chief Pontiac is buried. Historically significant for the military campaign he personally launched against the British in 1763 (the appropriately titled “Pontiac’s War”), Chief Pontiac was murdered near the village of Cahokia by a Peoria warrior in 1769. It’s believed his remains were brought over the river to St. Louis and interred in the ground near that intersection.

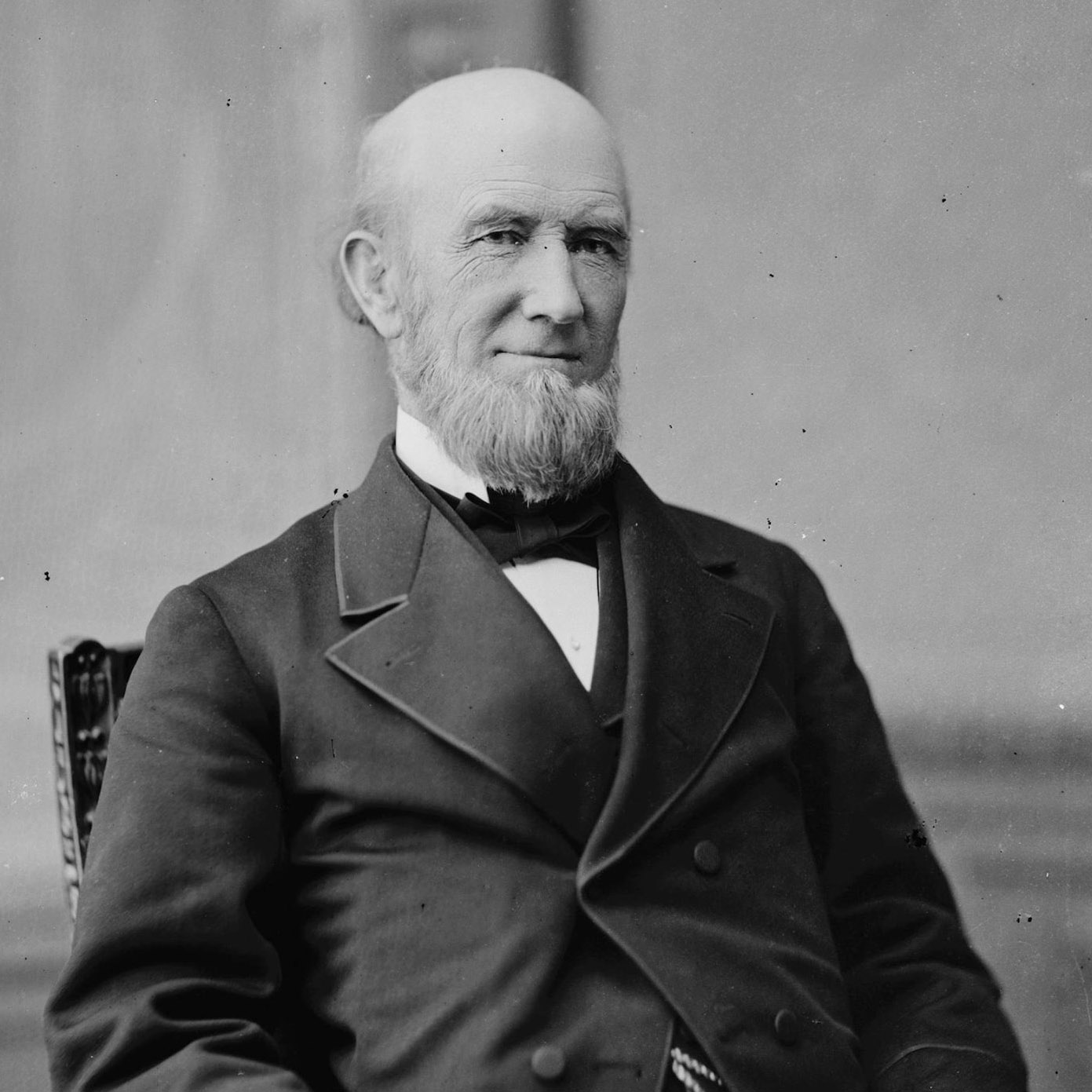

Those are pretty good reasons to stare at a corner and wonder what once happened there, but I think the magnificent Southern Hotel, which stood on that corner from 1865 until 1934, provides many more. I should also admit I’ve been boasting about the Southern Hotel for years. The guy who owned it from 1865 until 1877 is someone I’m a huge fan of. That man is Robert Campbell, and it his house (now known as the Campbell House Museum) that is the base of operations for this blog and where I spend time as a volunteer.

The idea behind the Southern Hotel’s construction, a project of several prominent city leaders in the 1850’s, was based in the belief that St. Louis required a world-class hotel as it rushed to become a world-class city. Profit was surely a motivation, but civic pride was the driving force behind this particular hotel. And when it opened in December 1865, the city celebrated. Marching bands played, governors visited, and glowing reports of the opening night’s gala were printed in newspapers across the nation. The Missouri Republican proclaimed it the “finest hotel in the world” and it was “the theme of many celebrated pens and tongues, both native and foreign”. It even became the subject of song: “The Southern Hotel Waltz”, which was published in 1865 by composer Albert Mahler.

The Southern Hotel occupied the entire block bounded by Walnut, 4th, 5th (now Broadway) and Elm Streets (of which Elm no longer exists in that part of the city). The principal front and entrance of the hotel faced Walnut Street, stretching 270 feet from one end to the other. The Southern was six stories tall, with an exterior made of “Chicago stone”, which the St. Louis Republican at the time described as “magnesian stone of excellent properties”. It contained over 350 guest rooms and apartments, and employed nearly the same number of people to keep it running. It was designed in the Italianate style by the famous St. Louis architect George Barnett, who’s other notable works included the Old Courthouse, Henry Shaw’s Tower Grove House, and the Grand Water Tower.

T o imagine what this special hotel looked like in its day, it’s important to note that the city of St. Louis at that time was a very crowded place. The population was almost exactly what it is today (about 320,000), but the city itself was much smaller. Before 1876, the city’s western boundary sat just a few hundred feet west of Grand Avenue, and Carondelet hadn’t been added yet. Although new neighborhoods had been developed away from the congested riverfront starting in the 1850’s, the city around the Southern Hotel remained densely populated. The neighborhood around the Southern was also a very upscale part of town. Grand homes and elegant buildings surrounded the hotel, especially to the north and west. It was a time when St. Louis was one of the biggest cities in America, and it could rival the glitz and glamour of cities like New York and Philadelphia.

o imagine what this special hotel looked like in its day, it’s important to note that the city of St. Louis at that time was a very crowded place. The population was almost exactly what it is today (about 320,000), but the city itself was much smaller. Before 1876, the city’s western boundary sat just a few hundred feet west of Grand Avenue, and Carondelet hadn’t been added yet. Although new neighborhoods had been developed away from the congested riverfront starting in the 1850’s, the city around the Southern Hotel remained densely populated. The neighborhood around the Southern was also a very upscale part of town. Grand homes and elegant buildings surrounded the hotel, especially to the north and west. It was a time when St. Louis was one of the biggest cities in America, and it could rival the glitz and glamour of cities like New York and Philadelphia.

The Southern was the most luxurious hotel in St. Louis, and if one wanted to be seen, the Southern was the place to be. If one stood on the corner of 4th and Walnut in the 1870’s, seeing a celebrated actress of the day, a business tycoon, or even a president walk through its doors would not have been a surprise. Inside, one could find Mark Twain playing billiards, Adolphus Busch sipping wine, or Ulysses S. Grant leaning against the Southern Hotel’s famous mahogany bar. In the hotel’s immense rotunda, Theodore Roosevelt, Oscar Wilde, or the famous actress Lily Langtry could stride by, all of whom were guests at the Southern at one time or another. And if one was fortunate to be invited, attending a lavish banquet in honor of a prominent citizen such as James Eads, Henry Blow, or Robert Campbell was a possibility.

Famous guests aside, the Southern Hotel was also the site of some remarkable events. The most tragic of them explains why there were actually two Southern Hotels. In the early morning hours of April 11, 1877, a fire broke out in the hotel’s basement. The result was a tragedy that rocked the city of St. Louis and became front-page news across the nation. Perhaps more than twenty guests and hotel employees were killed, many more were severely injured, and the original Southern Hotel was completely destroyed. However, the story of that fire is also remarkable for the bravery and heroism shown by the St. Louis Fire Department (and that story is coming up next in this blog).

Another amazing story is the Preller trunk murder. On April 12, 1885, the manager of the Southern Hotel checked room 144 after reports of a foul odor emanating from the room. Inside, he found the decomposing body of a man stuffed inside a trunk bound with rope. The victim, identified as Charles Arthur Preller, was found wearing nothing but a pair of white underwear with the name “H.M. Books” stitched into the waistband. A cross had been carved into Preller’s chest and a placard with the inscription “So perish all traitors to the great cause” was found along with the body. The subsequent trial of H.M Brooks (who had to be fetched from New Zealand) is so fantastic that I can’t do it justice here (in other words, Preller also gets his own future Distilled History post).

Along with fires and murders, the Southern provided the backdrop for a host of notable events. It’s at the Southern where a man named Logan Reavis argued that the capital of the United States should be moved from Washington D.C. to St. Louis. It’s where James Eads proposed building a ship railway across Mexico, and where William McKinley caused an uproar when he did something no other president had done before: he lit a cigarette in public. In a room at the Southern Hotel in 1888, Democrats decided to nominate Grover Cleveland for President. Eight years later, Republicans used the Southern to negotiate the nomination for William McKinley. The outlaw Jesse James was rumored to stay at the Southern Hotel during his visits to St. Louis under the alias “J.J. Howard”. He came often for the purpose of racing his horses at the St. Louis Jockey Club (and he was recalled as an excellent tipper). In the years prior to becoming a publishing icon, Joseph Pulitzer lived in rooms 305 and 306 at the Southern Hotel, and he was there on the night of the tragic fire. In an article written for the paper Pulitzer would own just two years later (the St. Louis Dispatch), it’s reported that Pulitzer had to flee the building “sans shirt, stockings, or anything else”.

Sports and recreation were also no stranger to the Southern. People gambled, drank, boasted, and challenged each other daily at the Southern Hotel. The hotel’s bar is where Adolphus Busch placed $100 bets that he could name any wine he sipped, and it’s where “Gentleman Jim” Corbett challenged John L. Sullivan for the heavyweight championship in 1892. The result of that bet was one of the most famous fights in boxing history, and the first match to require that gloves be worn by the heavyweight contenders. Even baseball can point to the Southern for some of its history. Newspaper accounts of the time reported that the Southern Hotel’s lobby is where two newspaper men helped the American League’s Ban Johnson and the National League’s John Brush settle their differences. As a result, an annual event known as the “World Series” would come to be.

After the fire in 1877, the Southern Hotel was rebuilt (eventually) and it opened again to great fanfare in 1881. The new version was bigger, fancier, and advertised as “completely fireproof”. This newer version of the Southern continued as the city’s premier hotel, and it thrived during exciting times such when the world came to St. Louis in 1904. But cultures change, cities change, and the glimmer of the Southern began to fade in the early 20th Century. Citing declining patronage, the Southern Hotel was closed for good on August 1, 1912. Despite immediate rumors that it would soon reopen as a hotel, be converted into an office building, or even turned into a beer garden, none of them came to fruition. The former Southern Hotel spent its final two decades mostly empty or sporadically utilized as an exhibition hall for automobile shows. Burdened by taxes they no longer wanted to pay, the owners announced in 1933 the building was to be demolished.

And just two years later, a shiny new Mobil gas station opened on a pretty remarkable corner in downtown St. Louis.

For someone like me (someone who spends way too much time thinking about how and what people were drinking 150 years ago), places like the Southern Hotel are special. Today, great bars can still be found at hotels, but it’s not quite the same. Hotels were social centers back then, and hotels were places where 19th Century drinkers went if they wanted something other than a shot of whiskey (see: saloon) or a stein of beer (see: beer garden). Specifically, it was hotel bars that helped usher in an increasingly popular form of drink in the late 19th Century: the cocktail. St. Louis’s most famous example of this is the Planter’s House Hotel, which stood on the other side of the Old Courthouse. That’s where Jerry Thomas, a man known as the “father of American mixology”, plied his trade in the mid-19th Century.

Today, good cocktail bars are ubiquitous, and I wasn’t exactly thrilled with the idea of passing one of them up in order to get a drink for this post. For one thing, parking is no fun for hotel drinking, especially at the many downtown St. Louis options. However, it’s only fitting that I make my way to a hotel bar and toast the Southern, so I chose the St. Louis Union Station’s Hilton Hotel. Thinking it’s probably closest I can get to the spaciousness and grandeur of the Southern Hotel in its prime, I can report that I wasn’t disappointed at all. Union Station’s Grand Hall, with all its tourists, light shows, and lack of cocktail snobbery (that I can provide), is a fun place to have a drink.

I ordered the New York Central Manhattan off the cocktail menu (of course), and I’ll admit I wasn’t disappointed with that, either. The price is ridiculous ($11 for Four Roses?), but I’m pleased to report it was stirred and served up without me asking for it that way.

Cheers to you, majestic Southern!

Key sources:

- The Campbell House Museum archives gave me enough material about the Southern Hotel to write a book about the Southern and everything that happened there. I’m considering it.

- “St. Louis’ Southern Hotel Fire of 1877” – Gateway Heritage, Fall 1985, pages 38-48

- Many of the anecdotes about stuff like Busch’s wine bets, Corbett’s challenge, and the presidential nominations came from newspaper articles “remembering” the Southern Hotel when it was demolished in the 1930’s. Someday, I’d like to go back and nail them down with primary sources, but I think that will have to wait for a bigger project (book) to do that. In the meantime, the September 8, 1933 and the August 15, 1934 editions of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch were a big help

- In researching this post, I probably dug through over one hundred newspaper articles from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, the Missouri Republican, the New York Times, and many others. I’m not going to list them all here, but if anyone would like a list, please contact me.

- More attention to sources will be given in my next post about the 1877 fire that destroyed the Southern Hotel

What an awesome story! I would love to read the book I hope you’ll write! Any idea of what happened to the Pontiac plaque?

Thank you! Sadly, I believe the plaque is lost. I read somewhere the DAR are still looking for it.

I MIGHT be wrong, but I think it’s on the side of a parking garage in downtown St Louis.

Irony: Chief Pontiac’s final resting place, the site of a parking garage.

Another stellar post in my favorite history blog…. Awesome!

I have an ancestor listed on the St. Louis,1870 US Fed Census, Ward 5, subdivision #10, as working at the laundry (hotel). The hotel keeper is listed as Chas. P. Warner. The name of the hotel is not given but I’m assuming its the Southern hotel.

1. Is this correct?

2. Did the employees live at the Southern too?

Does the record provide an address for the hotel or mention the Southern specifically? Employees did live in hotels at the time, but other hotels stood close by. The Planter’s House, for example, was just a block away.

Hi, I just came across this blog while doing genealogy research. In 1816, my 4th great grandfather William Sullivan purchased the half block from the south side of Walnut from Fourth to Fifth streets (the site of the Southern Hotel). He was St. Louis’ first justice of the peace.

Good Morning, I enjoyed your article and would like permission to use the photo of the old Southern Hotel in a book I am writing. I have a letter written in 1867 by a railroad owner who was staying in the hotel, for $300 a month. As he also had a wife and two adult sons staying with him perhaps the amount was not excessive.

Hi there! Glad you enjoyed the article. The image is property of the Campbell House Museum, mentioned in the article. Give them a call and I’m sure they’ll help you out.